FDA Approval Made Easy (Well, Easier): A Step-by-Step Guide

FDA Drug Approval Process: 5 Easy Steps

Understanding the Complex Path from Lab to Pharmacy

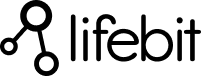

The FDA drug approval process is a rigorous, multi-stage journey that can take 10-15 years and cost over $1 billion to bring a single drug from laboratory findy to your local pharmacy. Here’s what you need to know:

The 5 Core Stages:

- Findy & Development – Laboratory research and compound identification

- Preclinical Research – Animal testing for safety and toxicity

- Clinical Research – Human testing in three phases (Phase 1, 2, and 3)

- FDA Review – New Drug Application (NDA) evaluation by FDA scientists

- Post-Market Safety Monitoring – Ongoing surveillance after approval

The process exists for one critical reason: to ensure that drugs available to Americans are both safe and effective. As one FDA case study explains, “The objective is to demonstrate the safety and efficacy of the drug or biologic for the proposed indication.”

Every prescribed drug in the U.S. has survived this gauntlet. The FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) acts as a consumer watchdog, ensuring that a drug’s benefits outweigh its risks before it reaches patients. Only about 1 in 1,000 compounds that enter laboratory testing ever make it to human trials, and roughly 9 out of 10 of those fail during clinical testing.

While the standard review takes 10 months, the FDA offers expedited pathways for breakthrough therapies and serious conditions. Priority Review can cut this to 6 months, and programs like Fast Track and Accelerated Approval help promising treatments reach patients faster.

I’m Maria Chatzou Dunford, CEO and Co-founder of Lifebit, where I’ve spent over 15 years working with pharmaceutical organizations to steer complex regulatory landscapes through secure, federated data analysis platforms. My experience in computational biology and health-tech entrepreneurship has given me deep insights into how the FDA drug approval process intersects with modern data analytics and AI-powered drug findy.

Basic fda drug approval process vocab:

The Bedrock of U.S. Drug Safety: The FDA’s Mandate

Think about the last time you picked up a prescription at your pharmacy. You probably didn’t question whether that little bottle contained what the label claimed, or worry that it might harm you more than help. That confidence exists because of the FDA’s unwavering commitment to drug safety – a system built on decades of hard-learned lessons, often written in response to public health tragedies.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration didn’t always have the robust powers it wields today. Back in the early 1900s, companies could sell pretty much anything as “medicine” with wild, unproven claims. Snake oil salesmen weren’t just a colorful part of American folklore – they were a genuine public health menace. The first major step toward reform was the 1906 Pure Food and Drugs Act, which prohibited interstate commerce in adulterated and misbranded food and drugs. However, it didn’t require manufacturers to prove their products were safe or effective.

That changed after the Elixir Sulfanilamide tragedy of 1937. A drug company, seeking to create a liquid version of a new sulfa drug, used a toxic industrial solvent (diethylene glycol) as the base. Over 100 people, many of them children, died agonizing deaths. The public outcry led directly to the passage of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic (FD&C) Act of 1938. This landmark legislation, for the first time, required companies to submit evidence of a drug’s safety to the FDA before it could be marketed.

Two decades later, another crisis underscored the need for even stricter controls. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the drug thalidomide was widely prescribed in Europe as a sedative and to treat morning sickness. It led to thousands of babies being born with severe birth defects. In the U.S., an FDA medical officer named Dr. Frances Kelsey repeatedly refused to approve the drug, citing insufficient safety data. Her skepticism saved countless American families from tragedy and spurred Congress to pass the Kefauver-Harris Amendments of 1962. This pivotal law established the modern requirement: drugs must be proven both safe AND effective before reaching the market. No more guesswork, no more empty promises.

The FDA’s primary role today, executed by its Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), centers on one critical question: Do this drug’s benefits outweigh its known risks for the intended population? CDER is the FDA’s drug review powerhouse, a massive organization composed of specialized offices that handle everything from new drug applications and generic drugs to compliance and surveillance. Its teams of physicians, statisticians, chemists, pharmacologists, and other scientists work like medical detectives, carefully examining every piece of evidence that drug companies submit. They’re not just rubber-stamping applications – they’re conducting independent, unbiased assessments to ensure each drug truly helps patients more than it hurts them.

This rigorous approach to preventing quackery means that when your doctor prescribes a medication, both of you can trust the science behind it. The FDA doesn’t just approve drugs and walk away, either. They provide ongoing information to doctors and patients about how to use medicines safely and what to watch for, ensuring the benefit-risk balance remains favorable throughout a drug’s lifecycle.

Modern drug development increasingly relies on understanding complex biological data. Genomics plays a crucial role in how we find and develop new treatments, helping researchers identify which patients are most likely to benefit from specific therapies. The result? The U.S. has one of the world’s most trusted pharmaceutical systems. When you see “FDA approved” on a medication, you’re looking at years of rigorous testing and review designed to protect your health.

Deconstructing the FDA Drug Approval Process: The 5 Core Stages

Picture this: thousands of promising compounds enter a laboratory, but only one or two will ever make it to your medicine cabinet. This is the reality of the drug development funnel – a process so selective that it makes getting into Harvard look easy.

The FDA drug approval process starts with what scientists call a New Molecular Entity (NME) – essentially an active ingredient that’s never been available in the United States before. Think of it as a completely new player entering the game, not just a variation of something that already exists.

Before companies dive headfirst into expensive trials, they often schedule Pre-IND meetings with the FDA. These conversations are like getting directions before a long road trip – they help avoid costly wrong turns later. Smart companies use these meetings to clarify requirements, discuss the design of preclinical and clinical studies, and make sure they’re on the right track from the very beginning.

There’s another crucial player in this story: the Institutional Review Board (IRB). These independent panels of scientists, doctors, and everyday citizens act as ethical guardians, reviewing clinical trial protocols to ensure patient safety and rights are protected above all else. They’re the ones making sure no one gets hurt in the name of medical progress.

Step 1 & 2: Preclinical Research and the IND Application

Before any drug can touch human skin, it must survive the preclinical gauntlet. This is where promising compounds face their first major test in laboratory dishes (in vitro studies) and animal models (in vivo studies). Scientists are asking fundamental questions: Does this drug have the desired biological effect? Is it too toxic for human use?

The preclinical phase focuses heavily on pharmacology (how the drug affects the body) and toxicology (what harm it might cause). Researchers conduct a battery of tests to understand the drug’s profile, including:

- Pharmacokinetics (PK): Studying what the body does to the drug—how it is absorbed, distributed, metabolized, and excreted (ADME).

- Pharmacodynamics (PD): Studying what the drug does to the body—its mechanism of action and relationship between drug concentration and effect.

- Toxicity Studies: Assessing potential harm through single-dose (acute) and repeated-dose (chronic) studies. These tests identify which organs might be targeted by toxicity and determine if the harmful effects are reversible. Multiple animal species (typically one rodent and one non-rodent) are used because what’s safe for a mouse isn’t always safe for humans.

All preclinical lab studies must comply with the FDA’s Good Laboratory Practices (GLP) regulations, which ensure the quality and integrity of the data submitted. Here’s the sobering reality: fewer than 1 in 1,000 compounds that start preclinical testing will ever reach human trials. Most fail because they’re either ineffective or unacceptably toxic.

For the lucky few that show promise, the next step is preparing an Investigational New Drug (IND) application. This comprehensive document, often hundreds of pages long, tells the FDA everything they need to know to evaluate the safety of the proposed human studies. It includes all animal pharmacology and toxicology data, detailed information about the drug’s Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls (CMC), and the complete clinical protocol for human testing.

The FDA then has 30 days to review the IND application. During this crucial window, FDA scientists determine whether the proposed studies would put human volunteers at unreasonable risk. If they have serious concerns, they can issue a clinical hold – a red light that stops all human testing until the sponsor addresses the problems. If the 30 days pass without a hold, the sponsor gets the green light to begin human trials.

At Lifebit, we’re constantly exploring how AI-driven approaches can help identify the most promising drug candidates even earlier in this process. More info about AI in Drug Findy

Step 3: Navigating the Clinical Trial Maze

Once the IND gets the green light, we enter the most critical and expensive phase of the FDA drug approval process: human clinical trials. This stage typically consumes 6-7 years and represents the make-or-break moment for most drug candidates.

Informed consent is the non-negotiable cornerstone of ethical clinical trials. Before anyone can participate, they must be given a detailed explanation of the study, including its purpose, procedures, potential benefits, and all foreseeable risks. They must fully understand what they’re signing up for, and they have the right to withdraw at any time. IRBs carefully review these consent documents to ensure they’re clear, comprehensive, and not coercive.

Clinical trials follow a carefully orchestrated progression through three main phases, each with a different primary question:

Phase 1: Is it safe?

These are the first-in-human studies, typically involving 20-80 healthy volunteers or, in some cases like oncology, patients with the target disease. Lasting about a year, the primary goal isn’t to cure anyone—it’s to assess safety, determine a safe dosage range, and understand how the human body processes the drug (pharmacokinetics). Researchers start with very low doses and escalate them carefully, watching for side effects and collecting data on the drug’s ADME profile.

Phase 2: Does it work?

Shifting the focus to effectiveness, Phase 2 studies involve a larger group of 40-300 patients who actually have the condition the drug is meant to treat. These studies, lasting around two years, provide the first real glimpse of whether the drug has a therapeutic effect (often called “proof-of-concept”). They also continue to gather safety data and help researchers refine the dosage for larger trials. Many Phase 2 studies are randomized and controlled, often using a placebo (an inactive look-alike pill) or an existing standard treatment as a comparator to ensure any improvements are truly due to the drug.

Phase 3: Is it better than what we have?

These are the grand finale before FDA submission. Phase 3 trials are large-scale, multicenter (often global) studies involving hundreds to 3,000 patients, typically running for three or more years. They are designed to provide the definitive, statistically significant evidence—the “substantial evidence” required by law—that the drug is both safe and effective for its intended use. These pivotal trials often compare the new drug directly against the current standard of care to answer the crucial question: Is this new treatment a meaningful improvement? The FDA is increasingly emphasizing the need for these trials to include diverse patient populations that reflect the real world in terms of age, race, and ethnicity.

The clinical trial process is complex, and patient recruitment remains one of the biggest challenges. We’re deeply involved in understanding how to optimize these processes. More info about Clinical Trial Recruitment

For a deeper understanding of why clinical trials are so crucial, check out Part 1: Understanding Clinical Trials – Why Are They Important for Drug Development?

Step 4: The New Drug Application (NDA) and Final FDA Review

After successfully navigating all three phases of clinical trials, drug sponsors face their final challenge: compiling a New Drug Application (NDA). This is not a simple form; it’s a massive, comprehensive submission that can run to thousands of pages, containing every piece of data collected during the drug’s development journey.

The NDA includes everything: all preclinical animal data, all human clinical trial data (both safety and efficacy), detailed information about the drug’s pharmacokinetics, comprehensive manufacturing details (the CMC section), and the company’s proposed labeling. This labeling becomes the official package insert if approved, telling doctors and patients exactly how to use the drug safely and effectively.

The FDA has 60 days from receipt to decide if the NDA is complete enough to review. If critical information is missing, they can issue a “refuse to file” letter, sending the application back to the drawing board.

Once accepted, an independent team of FDA scientists begins their comprehensive review. They’re asking the big questions: Is this drug safe and effective for its proposed use? Do the benefits outweigh the risks? Is the proposed labeling accurate and helpful? Are the manufacturing methods adequate to ensure the drug’s identity, strength, quality, and purity?

For many novel drugs, the FDA will convene an Advisory Committee meeting. These committees are composed of external experts (physicians, statisticians, patient representatives) who provide independent advice on the drug’s approvability. While the FDA is not bound by the committee’s vote, it takes their recommendations very seriously.

Thanks to the Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA), the FDA has specific timeline goals. Standard Review aims for a decision within 10 months, while Priority Review – reserved for drugs that represent significant improvements – targets just 6 months.

At the end of the review, the FDA issues either an approval letter (congratulations, you can now market your drug!) or a Complete Response Letter detailing exactly what deficiencies need to be addressed before approval can be granted.

Step 5: Post-Market Safety Monitoring (Phase 4)

Approval is not the end of the story. The FDA’s oversight continues for as long as a drug is on the market through post-market surveillance, often called Phase 4 of clinical development. This final stage is crucial for understanding a drug’s long-term safety and effectiveness in a real-world setting.

Phase 3 trials, while large, cannot detect very rare side effects that might only appear when millions of people use a drug. Post-market monitoring is designed to catch these signals. Key components include:

- Phase 4 Commitment Studies: The FDA can require a company to conduct further studies after approval to gather more information on a drug’s risks, benefits, and optimal use.

- FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS): This is a database that contains millions of adverse event reports submitted by healthcare professionals, consumers, and manufacturers. FDA scientists monitor FAERS for safety signals—new or more frequent side effects not seen in clinical trials.

- Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS): For drugs with known serious risks, the FDA can require a REMS to ensure the benefits of the drug outweigh its risks. This can range from a simple medication guide for patients to complex requirements like special physician training or patient monitoring.

If a serious safety issue is identified after approval, the FDA has several tools at its disposal. It can work with the manufacturer to update the drug’s label with new warnings, restrict its use, or, in the most serious cases, take action to remove the drug from the market entirely.

Accelerating Access: Expedited Pathways and Special Cases

When patients are facing serious or life-threatening conditions, waiting years for new treatments simply isn’t an option. The FDA understands this urgency and has created several expedited pathways to fast-track promising therapies without compromising its rigorous safety and efficacy standards.

Think of these programs as express lanes on the highway of drug development. They’re designed for drugs that address unmet medical needs – conditions where no effective treatment exists or where the proposed drug could be a significant improvement over current therapies. These pathways can cut years off the traditional timeline, potentially bringing life-saving medications to patients much sooner.

One important designation worth mentioning is Orphan Drug Designation. This applies to treatments for rare diseases affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S. annually. Since developing drugs for small patient populations presents unique financial challenges, this designation provides powerful incentives like tax credits for clinical trials, waived FDA fees, and seven years of market exclusivity upon approval, independent of patent life.

| Designation | Purpose | Timing/Review Goal | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fast Track | Facilitate development for serious conditions with unmet needs | Rolling review allowed | Submit NDA sections as completed; more frequent FDA communication |

| Breakthrough Therapy | Speed development when drug shows substantial improvement over available therapy | All Fast Track benefits plus intensive guidance | More frequent FDA meetings; senior FDA management involvement |

| Priority Review | Faster FDA review for drugs offering significant improvements | 6-month review goal (vs. 10-month standard) | Focuses on the NDA review period, not development |

| Accelerated Approval | Earlier approval based on surrogate endpoints for serious conditions | Variable, depends on confirmatory trials | Post-market studies are required to verify clinical benefit |

Expedited Programs: Fast Track, Breakthrough Therapy, and Priority Review

These three programs work like a graduated system, each offering increasing levels of support and acceleration based on a drug’s potential impact.

Fast Track Designation is the most accessible of these pathways. It’s for drugs treating serious conditions with an unmet medical need. The real game-changer here is rolling review, which allows companies to submit portions of their New Drug Application as they’re completed rather than waiting for the entire package. This means the FDA can start reviewing safety and manufacturing data while the final efficacy studies are still ongoing, creating a more collaborative and efficient process.

Breakthrough Therapy Designation raises the bar significantly. Introduced in 2012, this designation requires preliminary clinical evidence showing the drug may offer substantial improvement over existing treatments on one or more clinically significant endpoints. It includes all Fast Track benefits but adds intensive FDA guidance and a more collaborative, all-hands-on-deck approach from the agency. For example, the cancer immunotherapy drug Keytruda (pembrolizumab) received this designation, which helped accelerate its approval for multiple cancer types, changing treatment paradigms.

Priority Review focuses solely on the final FDA review stage. It doesn’t speed up the clinical trials, but it sets an agency goal to take action on an application within 6 months, compared to the standard 10 months. This designation is granted to drugs that, if approved, would be significant improvements in the safety or effectiveness of the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of serious conditions. A drug can receive both Breakthrough Therapy designation during development and Priority Review at the time of submission.

The precision medicine revolution is making these pathways increasingly important, as we’re seeing more targeted therapies that can dramatically improve outcomes for specific patient populations. More info about Precision Medicine

Accelerated Approval: Balancing Speed and Certainty

Accelerated Approval represents perhaps the most innovative approach to balancing speed with safety in the fda drug approval process. This pathway allows the FDA to approve drugs for serious conditions based on surrogate endpoints—measurable changes (like tumor shrinkage or a change in a blood test marker) that are reasonably likely to predict a real clinical benefit (like living longer or feeling better), even if that ultimate benefit hasn’t been definitively proven yet.

This approach has been particularly valuable for life-threatening diseases like HIV/AIDS and cancer. Many of today’s standard HIV treatments first reached patients through Accelerated Approval based on their ability to reduce viral load, allowing people to access life-saving medications years earlier than would have been possible otherwise.

The critical trade-off is that companies receiving Accelerated Approval must conduct confirmatory trials after approval to verify that the surrogate endpoint truly translates into real clinical benefit. This pathway has faced scrutiny, particularly in cases where confirmatory trials are delayed or fail to show the expected benefit. The controversy surrounding the 2021 approval of Aduhelm for Alzheimer’s disease, based on the surrogate endpoint of amyloid plaque reduction, highlighted the intense debate over the appropriate use of this pathway and has led to increased FDA focus on ensuring confirmatory studies are completed in a timely manner. If post-market studies fail to confirm clinical benefit, the FDA can withdraw the approval.

Understanding how we define and measure success in clinical trials is crucial for appreciating these pathways. Learn more about how we define success for clinical trial

Streamlined Pathways: Generics, OTCs, and Medical Devices

Not all medical products follow the same exhaustive approval pathway. Generic drugs, over-the-counter (OTC) medications, and medical devices each have their own streamlined processes that reflect their unique risk profiles and regulatory needs.

Generic drugs follow a much shorter path through an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). Since the safety and efficacy of the original brand-name drug have already been established through decades of use and a full NDA, generic manufacturers only need to prove bioequivalence. This means demonstrating through scientific studies that their version delivers the same amount of active ingredient to the bloodstream at the same rate as the original. This process typically takes months rather than years and costs a fraction of the original drug’s development budget. To incentivize generic competition, the first company to submit a successful ANDA is often granted a 180-day period of market exclusivity. Facts about generic drugs

Over-the-counter drugs can come to market in two ways. Many common OTC ingredients (like aspirin or ibuprofen) are governed by OTC Monographs. These are essentially recipe books developed by the FDA that specify which ingredients, doses, formulations, and labeling are generally recognized as safe and effective for specific conditions. As long as a manufacturer follows the monograph, they don’t need a pre-market approval for their product. New OTC drugs, or those switching from prescription to OTC status, typically require a full NDA.

Medical devices use an entirely different system based on risk classification:

- Class I devices (lowest risk, e.g., bandages, tongue depressors) are subject to general controls like proper manufacturing and labeling, but most are exempt from premarket review.

- Class II devices (moderate risk, e.g., infusion pumps, blood pressure monitors) typically use the 510(k) pathway, where the manufacturer demonstrates the new device is “substantially equivalent” to a legally marketed predicate device.

- Class III devices (highest risk, e.g., pacemakers, heart valves) require a full Premarket Approval (PMA) application, which is similar to an NDA and requires clinical data to prove safety and effectiveness.

For novel, low-to-moderate risk devices that don’t have a predicate, the FDA has a De Novo classification pathway that allows for a risk-based review.

These varied pathways reflect a fundamental principle of the fda drug approval process: the level of scrutiny must always be appropriate to the level of risk.