Decoding the complex world of health data ecosystems

Health data ecosystem broken: avoid repeat tests and care delays

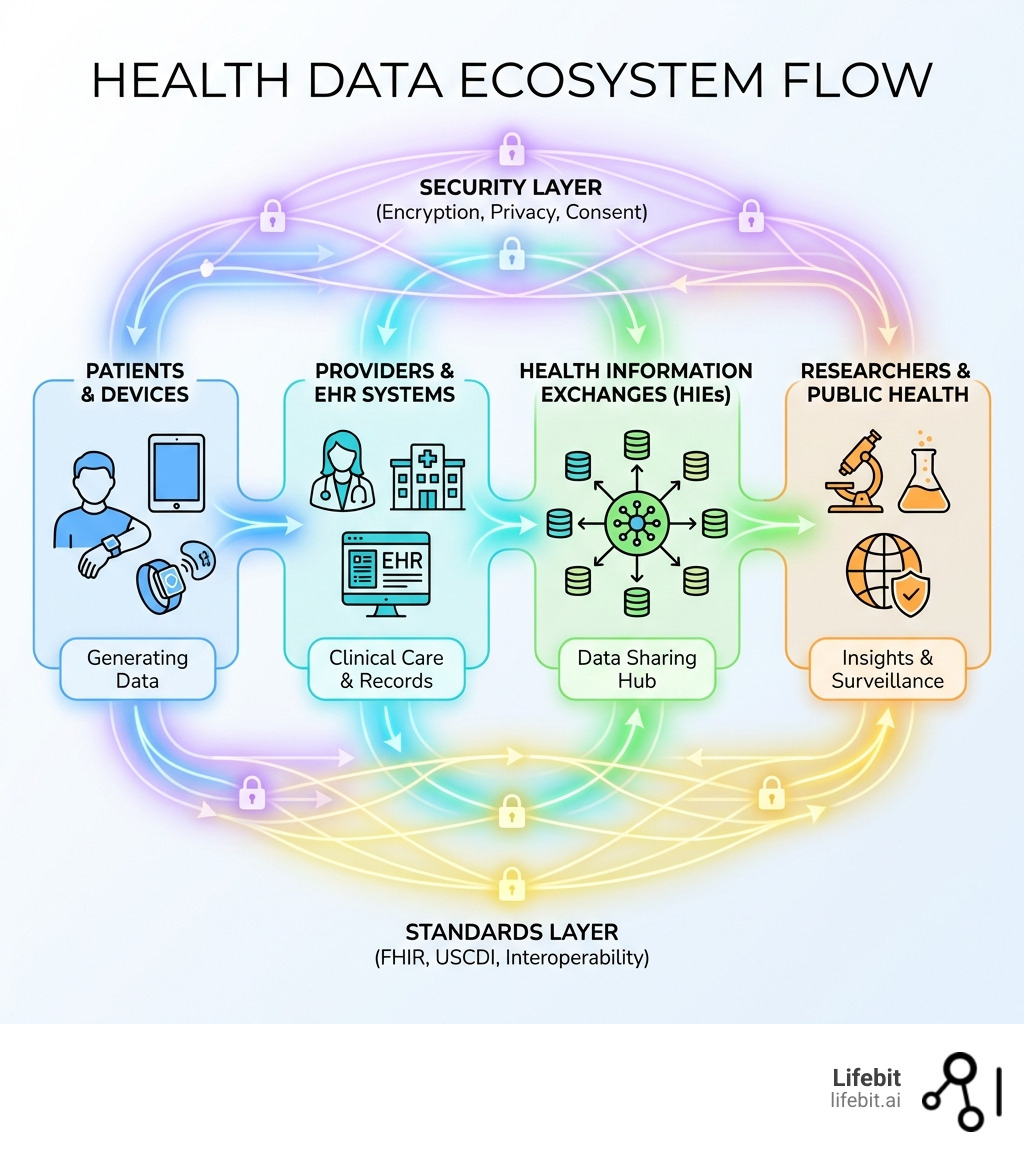

The health data ecosystem is the interconnected network of systems, standards, stakeholders, and regulations that enable the collection, exchange, and use of health information across healthcare providers, researchers, patients, payers, and technology companies. In the modern era, this ecosystem has evolved from a collection of isolated paper records into a complex, digital-first infrastructure that underpins every aspect of modern medicine. However, despite the rapid digitization of healthcare, the ecosystem remains fundamentally fragmented, leading to a “data paradox”: we are generating more health data than ever before, yet clinicians and researchers often lack the specific, actionable insights they need at the point of care or discovery.

Core Components:

- Standards & Infrastructure: FHIR (Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources), USCDI (United States Core Data for Interoperability), and TEFCA (Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement). These form the technical and legal backbone that allows disparate systems to communicate.

- Key Stakeholders: Patients (the primary data owners), healthcare providers (hospitals, clinics), tech companies (EHR vendors, wearable manufacturers), researchers (academic and biopharma), government agencies (CDC, ONC), and payers (insurance companies).

- Primary Functions: Clinical care coordination, population health management, research and innovation, and public health surveillance. A mature ecosystem ensures that data flows seamlessly between these functions to create a continuous learning loop.

- Major Regulations: HIPAA (US), GDPR (EU), and the emerging European Health Data Space (EHDS). These regulations act as the guardrails, balancing the need for data utility with the absolute requirement for individual privacy and security.

Current State (2023 Data):

- 70% of US hospitals engage in all four domains of interoperable exchange (send, receive, find, integrate).

- Only 43% routinely engage in full interoperability, highlighting a significant gap between capability and daily practice.

- 71% have access to external clinical information, but just 42% of clinicians use it regularly, often due to poor data quality or integration within the clinical workflow.

- Significant disparities exist between large urban hospitals (53% routine engagement) and small rural facilities (38%), creating a digital divide that impacts patient equity.

The challenge? While electronic health records (EHRs) are now widespread, actually accessing and exchanging that data remains frustratingly difficult. Hospitals struggle to share information with long-term care facilities (only 16% send records to most providers) and behavioral health centers (17%). Clinicians have data available but don’t use it because it is often presented as a “data dump” rather than curated, relevant information. Systems don’t talk to each other, leading to redundant testing, medical errors, and delayed diagnoses.

This fragmentation costs lives, wastes billions in unnecessary administrative overhead, and slows medical innovation by keeping valuable research data locked in silos. The solution requires more than technology—it demands new governance models, ethical frameworks, and collaborative approaches that balance innovation with privacy. As digital health meets digital capitalism, questions about data ownership, consent, and the common good become critical.

I’m Maria Chatzou Dunford, CEO and Co-founder of Lifebit, where I’ve spent over 15 years building federated genomics and biomedical data platforms that enable secure, compliant analysis across the health data ecosystem. My work focuses on breaking down data silos through federated AI, empowering researchers and clinicians to open up insights without moving sensitive patient information. By bringing the analysis to the data, rather than the data to the analysis, we can finally bridge the gap between data generation and medical breakthrough.

Health data ecosystem terms at a glance:

- I’m looking for services that provide access to anonymized patient data for research purposes.

- biomedical data access

- cloud computing healthcare

The Current State of the Global Health Data Ecosystem

The global health data ecosystem is undergoing a massive shift. We have moved from a world of paper charts to one where 96% of hospitals use certified electronic health records (EHRs). However, having the data is not the same as using it. According to the 71 Interoperable Exchange of Patient Health Information Among U.S. Hospitals: 2023 report, while 70% of hospitals engage in the four domains of interoperability (sending, receiving, finding, and integrating data), there is a significant “routine engagement” gap. This gap suggests that while the technical plumbing exists, the operational and cultural shifts required to make data sharing a standard part of care have not yet fully materialized.

Only 43% of hospitals routinely perform all four functions. This means that for more than half of the healthcare system, data sharing is an occasional event rather than a standard part of the clinical workflow. This inconsistency leads to fragmented patient longitudinal records, where a specialist may not see the results of a test performed by a primary care physician, leading to duplicate procedures and increased costs.

The Clinician Utilization Gap

One of the most startling statistics from 2023 is that while 71% of hospitals report having routine access to necessary clinical information from outside providers, less than half (42%) of clinicians actually use that information when treating patients. This suggests a profound “usability crisis.” The data being received is often difficult to find within the EHR, poorly formatted, or irrelevant to the immediate care decision. Clinicians, already burdened by high administrative loads, cannot afford to spend minutes searching through hundreds of pages of unstructured PDFs to find a single lab result. To fix this, the ecosystem must move toward “semantic interoperability,” where data is not just exchanged but is also understandable and actionable by the receiving system.

Disparities in the Ecosystem: The Digital Divide

The ecosystem is not evolving at the same speed for everyone. Large, system-affiliated hospitals are significantly more likely to be fully interoperable (53%) compared to independent hospitals (22%). Small and rural hospitals face even steeper climbs; roughly 2 in 5 rural and critical access hospitals are not fully interoperable today. This “digital divide” risks leaving certain patient populations behind. Patients in rural areas may receive care based on incomplete medical histories, while those in wealthy urban centers benefit from highly integrated, data-driven care. This disparity is often driven by the high cost of EHR implementation, a lack of specialized IT staff in rural areas, and the financial strain on independent practices.

Key Components of the Health Data Ecosystem

To fix this fragmentation, the US government and international bodies have established several “building blocks” designed to create a unified framework for data exchange. These are not just technical standards; they are the foundational rules of the road for the digital health era.

- FHIR (Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources): This is the modern “language” of healthcare. Developed by HL7, FHIR allows different systems to talk to each other using standardized APIs, much like how different apps on your phone can share information. It uses modern web technologies (RESTful APIs) to make health data as accessible and easy to use as any other digital service.

- USCDI (United States Core Data for Interoperability): This is a standardized set of health data classes and constituent data elements (like medications, lab results, and clinical notes) that must be available for nationwide exchange. It ensures that when data is sent, the receiver knows exactly what they are looking at, reducing the need for manual data entry and reconciliation.

- TEFCA (Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement): Think of this as the “interstate highway system” for health data. It provides the legal and technical rules that allow different health information networks (HINs) to connect securely. By establishing Qualified Health Information Networks (QHINs), TEFCA aims to create a single on-ramp to nationwide connectivity, eliminating the need for hospitals to join dozens of different networks.

- Implementation Centers: As part of the federal About Public Health Data Interoperability strategy, these centers help public health jurisdictions transition to modern data standards. This ensures that data doesn’t just stay in the hospital but helps protect the whole community by enabling real-time disease surveillance and outbreak response.

Overcoming Challenges in the Health Data Ecosystem

The primary challenge remains data fragmentation. Health data is generated everywhere—from hospitals and doctor’s offices to smartwatches, consumer apps, and even social services. This expansion means we are dealing with new types of data (unstructured text, genomic sequences, high-resolution imaging) and new stakeholders who aren’t traditional medical providers.

To manage this, we must prioritize Privacy by Design. This means building security and consent into the very architecture of our systems, rather than treating them as an afterthought. We also need to address the social determinants of health (SDOH). A truly robust health data ecosystem doesn’t just track your blood pressure; it understands your housing situation, your access to healthy food, and your local environment. Integrating this non-clinical data is essential for moving from reactive treatment to proactive prevention.

| Feature | Primary Data Use | Secondary Data Use |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Direct patient care and treatment | Research, policy, and public health |

| User | Doctors, nurses, patients | Researchers, government, biopharma |

| Privacy | HIPAA/GDPR (Identified) | De-identified or Pseudonymized |

| Regulation | Clinical guidelines | EHDS / Data Act / Research Ethics |

| Data Type | Real-time, high-granularity | Aggregated, longitudinal |

| Access Model | Point-of-care access | Trusted Research Environments (TREs) |

Navigating Global Regulations: HIPAA, GDPR, and the EHDS

Regulations are the guardrails of the health data ecosystem. They define who can access data, for what purpose, and under what conditions. In the US, HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) has governed privacy for decades. However, HIPAA was written in 1996, long before the age of smartphones, cloud computing, and massive AI-driven datasets. While it has been updated, it primarily covers “covered entities” like hospitals and insurers, leaving a vast amount of consumer-generated health data (from apps and wearables) in a regulatory gray area.

In Europe, the GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) set a high bar for data protection globally. It treats health data as a “special category” of sensitive information, requiring explicit consent for processing unless specific exemptions apply. GDPR also introduced the “Right to Portability,” giving patients the right to receive their data in a machine-readable format and transfer it to another provider. This has been a major catalyst for interoperability efforts across the continent.

The most significant new development is the European Health Data Space Regulation (EHDS). Approved in 2024, the EHDS is a pioneering initiative that aims to create a genuine single market for digital health. It focuses on two main pillars:

- Primary Use: Empowering patients to access and share their health data across all EU member states, ensuring that a patient from Spain can have their records accessed by a doctor in Germany during an emergency.

- Secondary Use: Facilitating the use of health data for research, innovation, and policy-making. It establishes a framework where researchers can request access to large-scale, pseudonymized datasets through a centralized body, reducing the administrative burden of negotiating with individual hospitals.

For companies and researchers, the EHDS is a game-changer. It mandates that healthcare institutions meet standards for secondary data use by 2028. This will allow researchers to access data in Trusted Research Environments (TREs)—secure digital spaces where data can be analyzed without ever being downloaded or moved. This “data stays, code flies” approach balances the need for high-speed innovation with the absolute requirement for patient privacy. It also addresses the issue of “data hoarding,” where institutions refuse to share data for research purposes, by making data sharing a regulatory requirement under specific conditions.

Ethics and the Rise of Digital Health Capitalism

As health data becomes more valuable—often described as the “new oil” of the 21st century—we face a growing tension between “public good” and “private profit.” This is often referred to as the meeting of digital health and digital capitalism. The commercialization of health data offers immense potential for developing new drugs and AI diagnostics, but it also raises profound ethical questions about who truly benefits from this data.

The expansion of the health data ecosystem beyond traditional clinics into consumer devices (like Oura rings, Apple Watches, or continuous glucose monitors) creates new ethical dilemmas. Who owns the data generated by your heart rate monitor? While you may “own” the device, the data is often stored on proprietary servers owned by tech giants. If a tech company uses your data to develop a new AI diagnostic tool that generates billions in revenue, do you, as the data generator, share in that benefit? Currently, the answer is almost always no.

In the bookcast The Platform Society: Public Values in a Connective World, experts discuss how “platformization” can destabilize public values like solidarity and the common good. There is a risk of power asymmetries, where a few large tech companies control the vast majority of health data. These companies can act as “gatekeepers,” potentially excluding smaller academic researchers or public health agencies from accessing the very data needed to solve public health crises. This concentration of data power can also lead to “algorithmic bias,” where AI tools are trained on data that does not represent the full diversity of the human population.

To counter these risks, we advocate for Responsible Data Science. This is not just about following the law; it’s about building a system that is inherently fair and transparent. Key pillars include:

- Informed Consent 2.0: Moving beyond the traditional “check-the-box” forms that no one reads. We need dynamic consent models where patients can choose how their data is used in real-time, and can withdraw that consent just as easily.

- Data Solidarity: This concept suggests that data sharing should be viewed as a collective responsibility that benefits the community, particularly underserved populations. It moves the focus from individual ownership to collective benefit.

- Data Sovereignty: Giving individuals and communities—especially indigenous and marginalized groups—more control over their digital footprints. This ensures that data is not extracted from these communities without their participation and benefit.

- Transparency and Auditability: Ensuring that the algorithms used to analyze health data are transparent and can be audited for bias. If an AI makes a clinical recommendation, we must be able to understand why it made that choice.

Future Directions: Integrated Care and Rapid Learning Systems

The ultimate goal of a mature health data ecosystem is the creation of a Rapid Learning Health System (RLHS). In this model, the traditional boundary between clinical practice and medical research disappears. Every patient interaction generates data that is immediately used to improve care for the next patient. It creates a continuous, virtuous loop where real-world evidence (RWE) informs clinical guidelines in weeks rather than years.

Population Health Management and AI

By integrating data from clinical care, public health, and social services, we can move from “sick care” (treating people after they become ill) to true “health care” (keeping people healthy). This involves using AI to identify high-risk populations before they get sick. For example, by analyzing patterns in EHR data, social determinants (like zip code or food security), and wearable data, health systems can intervene with a pre-diabetic patient months before they require insulin. This shift requires a move away from “fee-for-service” models toward “value-based care,” where providers are rewarded for keeping patients healthy rather than for the volume of tests they perform.

Digital Twins and In Silico Trials

One of the most exciting future directions is the development of “Digital Twins”—virtual models of individual patients. By combining genomic data, clinical history, and real-time sensor data, doctors could test different treatments on a patient’s digital twin before prescribing them in real life. This would revolutionize personalized medicine, particularly in oncology and rare diseases. Furthermore, “In Silico” trials—clinical trials conducted entirely through computer simulation using ecosystem-wide data—could drastically reduce the time and cost of bringing new life-saving drugs to market.

PROMs and PREMs: The Patient Voice

We are also seeing a rise in Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) and Patient-Experience Measures (PREMs). Historically, the health system has focused on “objective” data like blood pressure or tumor size. However, a mature ecosystem must also capture the patient’s lived experience—their pain levels, their ability to perform daily tasks, and their satisfaction with their care. By integrating these subjective measures into the data stream, we ensure that the health system is actually delivering what matters most to the people it serves. This patient-centric approach is the final piece of the puzzle in creating a truly holistic health data ecosystem.

Frequently Asked Questions about Health Data Ecosystems

What is a health data ecosystem?

It is the collective network of people, technology, and rules that allow health information to flow securely between those who need it. It encompasses everything from your family doctor’s EHR to the cloud-based platforms used by genomic researchers. The goal is to ensure the right data is available to the right person at the right time to improve health outcomes.

How does TEFCA improve nationwide data exchange?

TEFCA (Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement) creates a “network of networks.” Instead of a hospital having to build separate digital bridges to every other hospital or insurance company, they connect to a Qualified Health Information Network (QHIN). These QHINs then connect to each other using a single set of legal and technical rules. This makes it easier for your medical records to follow you across state lines or between different hospital systems, much like how you can use any ATM to withdraw money from your bank account.

What are the primary barriers to routine interoperability?

The biggest barriers aren’t just technical; they are often financial and cultural. Many smaller hospitals lack the resources to upgrade their systems or hire the necessary cybersecurity experts. Furthermore, some providers still view data as a competitive asset they want to hold onto—a practice known as “information blocking.” While the 21st Century Cures Act has made information blocking illegal, changing the culture from “data ownership” to “data stewardship” takes time.

Is my data safe in a global health data ecosystem?

Security is a foundational component of the ecosystem. Modern systems use advanced encryption, multi-factor authentication, and audit logs to track every time a record is accessed. Furthermore, new technologies like Federated Learning and Trusted Research Environments allow data to be analyzed without ever being moved or shared in its raw form, significantly reducing the risk of data breaches. However, as the ecosystem grows, patients must remain vigilant about which apps they grant access to their health data.

What is the role of the patient in this ecosystem?

In a mature ecosystem, the patient is the central hub. You should have the ability to access your full medical history on your smartphone, share it with new doctors, and even contribute it to research studies if you choose. The shift toward “patient-mediated exchange” means you are no longer a passive recipient of care but an active manager of your own health information.

Why Federated AI is the Key to Open uping the Ecosystem

At Lifebit, we believe the future of the health data ecosystem is federated. The old model of moving all data into one giant central database—the “data lake” approach—is increasingly obsolete. It’s too risky from a security perspective, too slow due to the massive size of modern datasets (especially genomics), and often illegal under strict residency regulations like GDPR or the upcoming EHDS.

Our Lifebit Federated Biomedical Data Platform represents a paradigm shift. Instead of moving data to the analysis, we bring the analysis to the data. Whether it’s genomic data in a secure server in London, clinical records in a hospital in New York, or lifestyle data in a cloud in Singapore, our platform enables secure, real-time collaboration without moving a single byte of raw patient data. This is achieved through a combination of federated learning, secure enclaves, and differential privacy.

The Benefits of a Federated Approach:

- Enhanced Security: Since the data never leaves the provider’s secure environment, the “attack surface” for hackers is significantly reduced. There is no central honey-pot of data to target.

- Regulatory Compliance: It allows for international research collaboration while strictly adhering to local data residency laws. Data stays within its jurisdiction, but insights can be shared globally.

- Scalability: As the volume of health data grows—driven by the explosion of biobanks and genomic sequencing—moving that data becomes physically and financially impossible. Federated AI allows us to analyze petabytes of data where they reside.

- Data Sovereignty: It allows hospitals and research institutions to maintain full control over their data. They can see exactly who is running what analysis and can revoke access at any time.

By embracing federated governance and advanced AI/ML analytics, we can finally turn the fragmented pieces of today’s health data into a unified engine for discovery. We are moving toward a world where a researcher in a small lab can query the world’s collective medical knowledge to find a cure for a rare disease, all while ensuring that every patient’s privacy remains absolute. The ecosystem is ready; it’s time to connect the dots and build a healthier future for everyone.