Bridging the Gaps: Strategies for Harmonizing Your Electronic Health Records

Stop Losing Millions to Broken EHRs: How Harmonization Turns Siloed Data into Real-World Evidence

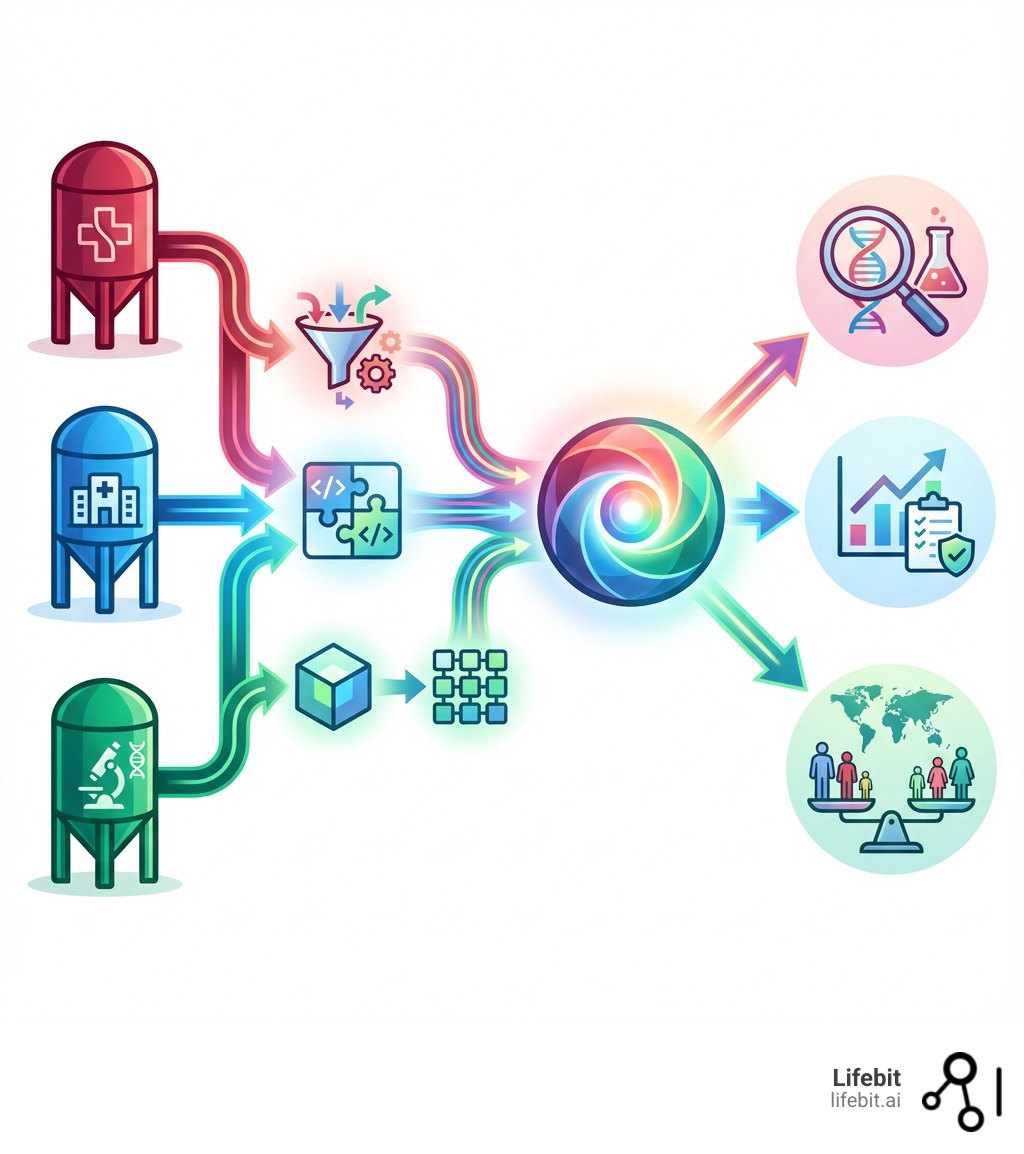

Harmonizing disparate electronic health records is the process of standardizing patient data from multiple, incompatible systems into a single, analyzable format. This opens up consistent data definitions, reliable population analysis, and reusable data mappings, ultimately improving research generalizability and delivering actionable insights into health disparities.

The challenge is urgent. EHRs hold a wealth of clinical data that could transform patient care, but accessing it is often “a daunting process,” stymied by institutional policies and inconsistent formatting. Without harmonization, researchers face duplicated work and wasted resources. One effort to analyze data from 240,214 patients was nearly derailed by formatting issues and incompatible codes. In contrast, a Wisconsin initiative successfully harmonized data from 25 health systems, enabling quality reporting for over 4 million patients.

The barriers are often organizational, not just technical. Different EHR vendors use conflicting standards for everything from clinical codes (Read V2 vs. SNOMED-CT) to basic demographic data. Yet progress is possible. Harmonization transforms fragmented data silos into a unified view of patient health, powering everything from comparative effectiveness research to real-time pharmacovigilance.

At Lifebit, we build next-generation federated platforms that enable harmonizing disparate electronic health records in secure environments without moving sensitive data. With components like our Trusted Research Environment (TRE), Trusted Data Lakehouse (TDL), and R.E.A.L. (Real-time Evidence & Analytics Layer), we help biopharma, governments, and public health agencies open up real-time, AI-powered insights from global biomedical and multi-omic data while maintaining strict privacy and compliance.

The Core Challenge: Why Your EHRs Don’t Talk to Each Other

The vision of a connected healthcare ecosystem remains aspirational because patient data is trapped in isolated “data silos.” This fragmentation is the primary challenge in harmonizing disparate electronic health records. The root cause is a lack of interoperability, where different systems cannot access, exchange, and use data in a coordinated way due to varying data standards—or no standards at all. This is not a single problem, but a multi-layered challenge spanning syntax, semantics, and structure.

Disparate EHRs struggle with:

- Syntactic Differences: This is the most basic level of incompatibility, involving inconsistent data formats and units. For example, dates may be recorded as ‘MM/DD/YYYY’, ‘YYYY-MM-DD’, or ‘DD-Mon-YY’. Lab values for weight might be in ‘lbs’ or ‘kg’, while cholesterol levels could be in ‘mg/dL’ or ‘mmol/L’. Without a standardized syntax, a simple query to find all patients over 65 becomes a complex programming task requiring custom logic for each data source.

- Semantic Ambiguity: This is a deeper challenge where the same term has different meanings across systems. The classic example is “gender,” which might refer to administrative gender in one system, biological sex in another, and gender identity in a third. This ambiguity has profound implications for research, potentially invalidating studies on sex-linked diseases. Another example is “family history of cancer.” Does this refer only to first-degree relatives? Does it include all cancer types or a specific one? Without a shared understanding of meaning (semantics), data cannot be reliably aggregated.

- Structural Heterogeneity: This refers to differences in the underlying data models. In one EHR, a diagnosis might be a single field containing an ICD-10 code. In another, it could be a complex “problem list” object with multiple attributes like

date_of_onset,diagnosing_physician,certainty_level(‘confirmed’ vs. ‘suspected’), andstatus(‘active’ vs. ‘resolved’). Harmonizing these requires not just mapping a value, but restructuring the entire data concept to fit a common model.

These barriers require extensive, often manual, effort to overcome, creating a significant bottleneck that delays critical research and hinders improvements in patient care.

Common Technical Problems in EHR Data Harmonization

The day-to-day work of harmonizing disparate electronic health records is fraught with technical problems that demand both domain expertise and sophisticated data engineering.

- Inconsistent Formatting and Units: Beyond dates, this issue plagues nearly every data type. Blood pressure might be a single text field ‘120/80 mmHg’ or two separate numeric fields, ‘Systolic: 120’ and ‘Diastolic: 80’. A potassium level could be recorded as “4.2”, “4.2 mEq/L”, or embedded in a free-text comment like “K+ is 4.2, stable.” Each variation requires custom parsing rules and unit conversion logic to standardize the data into a single, analyzable format.

- Missing Values and Imputation: Gaps in data are ubiquitous. A field like race/ethnicity can have over 50% missing data in some systems, crippling health equity research. It is crucial to understand why data is missing. Is it missing completely at random, or is the absence of data itself informative (e.g., a lab test wasn’t ordered because the patient was healthy)? Simply ignoring missing data can introduce severe bias. While techniques like multiple imputation can help fill gaps, they must be used with caution and a deep understanding of the underlying clinical context to avoid generating misleading results.

- Varied and Conflicting Coding Systems: Healthcare is a veritable alphabet soup of coding systems, each with a different purpose and level of granularity. Mapping between them is a core harmonization task.

- ICD (International Classification of Diseases): Primarily used for billing and administrative reporting. It is not granular enough for detailed clinical research (e.g., it can’t distinguish between different stages of a disease).

- SNOMED CT (Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine — Clinical Terms): The gold standard for clinical meaning. It is a comprehensive, hierarchical terminology designed to capture detailed clinical information in the EHR.

- LOINC (Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes): The standard for identifying lab tests and clinical observations. It answers the question, “What specific test was performed?”

- RxNorm: Normalizes drug names, linking brand names, generic names, and ingredients to a common vocabulary.

- Mapping is complex because there is often not a one-to-one correspondence. A single legacy code might map to multiple, more specific SNOMED CT codes, requiring clinical judgment to select the correct one.

- Data Entry Errors: Manual data entry is prone to human error. Common issues include transcription errors (typos), copy-and-paste errors (e.g., another patient’s notes being pasted into the wrong chart), errors of omission (leaving required fields blank), and errors of commission (selecting the wrong diagnosis from a dropdown). Data cleaning scripts and validation rules are essential to detect and flag these errors, such as an adult patient’s weight being recorded as 5 lbs or a lab value that is physiologically impossible.

- Lack of Standardization in Clinical Definitions: The clinical meaning of a concept can vary dramatically. Consider how to define a “smoker.” Is it a patient with a SNOMED code for “current smoker”? Someone with a social history checkbox marked “smoker”? Or someone with a free-text note saying “smokes 1 ppd”? A single patient record could contain conflicting information. Harmonization requires creating a clear, computable phenotype—a precise definition—from these disparate sources, a challenge the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) has addressed by creating standardized outcome measures.

These challenges show why harmonization is an ongoing process. For a deeper dive, see our post on Health Data Standardization Technical Challenges.

The High Cost of Data Inconsistency

The failure to harmonize disparate electronic health records is not just a technical inconvenience; it carries a substantial and multifaceted burden on the entire healthcare ecosystem.

- Wasted Research Funds: Researchers at different institutions are forced to independently clean and standardize similar datasets, duplicating effort and wasting millions in grant funding. This leads to smaller, less generalizable studies that have limited impact.

- Delayed Clinical Trials: Data cleaning and standardization is a major contributor to clinical trial timelines. According to the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development, data-related issues can account for a significant portion of trial delays, with each day of delay costing a sponsor millions in lost revenue and, more importantly, delaying patient access to potentially life-saving new treatments.

- Inaccurate and Burdensome Quality Reporting: Generating comparable quality measures across different health systems becomes a massive, manual task. US physician practices already spend more than $15.4 billion and 785 hours per physician annually on reporting quality measures, a cost massively exacerbated by underlying data inconsistencies.

- Hindered Public Health Response: The COVID-19 pandemic starkly illustrated this cost. Public health agencies struggled to get a clear, real-time picture of the pandemic because of disparate EHRs. Tracking hospitalizations, comorbidities, vaccination status, and breakthrough infections was severely impeded by the inability to quickly aggregate and analyze data from thousands of siloed systems.

- Missed Opportunities for Scientific Insight: The most profound cost is the lost opportunity. Trapped within these data silos are the signals that could lead to the next generation of precision medicine, the discovery of novel biomarkers for early disease detection, and a deeper understanding of health disparities. Fragmented data prevents us from seeing the big picture and uncovering the subtle trends that could transform medicine.

Data inconsistency is a drag on innovation and a fundamental barrier to achieving equitable care. Investing in Data Harmonization Overcoming Challenges is a strategic imperative for the future of healthcare.

A 5-Step Blueprint for Harmonizing Disparate Electronic Health Records

A structured, methodical approach can transform fragmented data into a powerful asset for research. This five-step blueprint provides a roadmap for harmonizing disparate electronic health records, emphasizing strategic planning, robust governance, and stakeholder collaboration. This is not merely a technical project but a strategic initiative that requires buy-in from across the organization.

Step 1: Define Clear Research and Quality Improvement Goals

First, articulate why you are harmonizing the data. Starting with a clear end goal ensures the effort is focused, measurable, and yields meaningful results. Vague goals like “improve research” are insufficient; goals must be specific and actionable.

- Identify Key Variables: Determine the essential data elements needed to answer your research question or calculate your quality metric (e.g., demographics, specific diagnoses, lab results, medication orders).

- Define Patient Cohorts: Specify the target population for your analysis using precise inclusion and exclusion criteria (e.g., “all patients over 50 diagnosed with Type 2 Diabetes, with at least two HbA1c measurements in the last 24 months”).

- Establish Outcome Measures: Define the specific patient outcomes you intend to measure. Whenever possible, use established standards like AHRQ’s harmonized outcome measures for conditions like atrial fibrillation and depression to ensure your results are comparable to other studies.

- Set Data Quality Thresholds: Decide on the acceptable level of data completeness and accuracy. For example, you might require that at least 95% of patients in your cohort have a value for a key variable like smoking status.

Assemble a Multidisciplinary Team: This goal-setting process must not happen in an IT vacuum. It requires a collaborative team of stakeholders: clinicians who can validate the clinical logic, researchers who define the study questions, data scientists who can assess technical feasibility, epidemiologists for population-level insights, and even patient representatives to ensure the work is relevant and ethical.

Step 2: Conduct Data Findy and Assessment

Next, investigate your source EHR systems to understand what data is available, its structure, and its quality. This “data findy” or discovery process is a critical prerequisite for planning a realistic harmonization project.

- Analyze Source Systems: Map out each EHR’s data model. Understand where relevant data resides (e.g., in structured fields, flowsheets, or unstructured notes), how it is stored, and any system-specific limitations or idiosyncrasies.

- Profile Data: Perform an initial quantitative assessment of the data. This involves analyzing value distributions, identifying formats, and cataloging inconsistencies. This step moves you from anecdotal knowledge (“the data is messy”) to a concrete, evidence-based understanding of the problem.

- Assess Completeness and Quality: Quantify missing values for key elements, paying special attention to crucial disparity indicators like race, ethnicity, and social determinants of health. As one collaborative found, missing data can be substantial, but high-quality information on disparity indicators can be achieved with careful assessment and targeted data quality initiatives. This step is crucial for Creating Research Ready Health Data.

Leveraging Data Profiling Tools and Techniques: This assessment can be accelerated using data profiling tools. Open-source libraries like pandas-profiling in Python or commercial platforms like Informatica Data Quality can automatically scan datasets and generate detailed reports on column statistics (min, max, mean), data types, value frequencies, and missing data percentages. These reports provide a quantitative baseline for the harmonization effort and help prioritize which data quality issues to tackle first.

Step 3: Select a Common Data Model (CDM) and Standardized Terminologies

A CDM provides a unified structure (or schema) for organizing clinical data, while standardized terminologies ensure that clinical concepts are uniformly coded. Together, they form the common language for your harmonized data. The choice of CDM is a strategic decision that should align with your goals from Step 1.

- Common Data Models (CDMs): Popular models include:

- OMOP (Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership): The leading standard for large-scale observational research. Its structure is optimized for executing cohort studies across federated networks. It is supported by the large OHDSI community, which provides a wealth of open-source tools. See our NIAID Data Harmonization OMOP Guide.

- HL7 FHIR (Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources): The modern standard for real-time data exchange between healthcare systems. Its API-based, resource-oriented structure is intuitive and flexible, but it was not originally designed for population-level analytics, which can be less efficient than on OMOP.

- CDISC (Clinical Data Interchange Standards Consortium): The global standard for submitting clinical trial data to regulatory agencies like the FDA. It is highly structured but often too rigid for messy, real-world observational data.

- openEHR: A flexible, two-level modeling approach that separates the technical data model from the clinical definitions (“archetypes”). This makes it highly adaptable and future-proof but can have a steeper learning curve.

- Standardized Terminologies: These provide the universal codes that populate the CDM. A CDM provides the structure (the tables and columns), while terminologies provide the content. Key examples are SNOMED CT for clinical findings, LOINC for lab observations, and RxNorm for medications.

Step 4: Execute Data Mapping and Transformation (ETL)

This is the technical core of the project, where raw, heterogeneous data is converted into the standardized CDM format through an Extract, Transform, Load (ETL) process.

- Extract: Securely retrieve or access raw data from source EHRs. In modern architectures, this is often done within a Trusted Research Environment (TRE) or via a federated platform to keep sensitive data secure at its source.

- Transform: This is the most complex and resource-intensive phase. It involves cleaning, standardizing, and reformatting the data. Key tasks include:

- Semantic Mapping: Aligning the meaning of local source concepts to standard terminology codes (e.g., mapping a local lab code “12345-K” for serum potassium to the correct LOINC code, 2823-3). This requires significant clinical domain expertise.

- Value Set Mapping: Standardizing permissible values (e.g., mapping ‘M’, ‘Male’, and ‘1’ all to a single standardized concept for male gender).

- Handling Unstructured Data: Using Natural Language Processing (NLP) to extract structured information (diagnoses, medications, symptoms) from unstructured clinical notes, which can contain up to 80% of relevant patient information.

- Running Data Cleaning Scripts: Applying programmatic rules to standardize date formats, convert units, flag or correct outlier values, and resolve logical inconsistencies.

- Load: Load the transformed, harmonized data into the target environment, such as a data warehouse, a dedicated analytics database, or a federated platform’s harmonized layer.

This process is iterative and can be streamlined with tools like our OMOP Mapping Free Offer.

Step 5: Implement Quality Control and Ongoing Governance

Harmonization is not a one-time project; it is an ongoing commitment to data quality. The final step is to implement rigorous quality control processes and a robust governance framework to maintain the value of the harmonized data over time.

- Data Validation: Implement automated and manual checks to ensure the transformed data is fit for purpose. This includes schema validation (does the data conform to the CDM?), value validation (are values within expected ranges?), and clinical plausibility checks (e.g., a patient should not have a clinical event dated after their date of death).

- Iterative Refinement: Use validation results to create a feedback loop, continuously refining mapping rules and cleaning scripts to improve data quality with each ETL cycle.

- Documentation and Metadata Management: Maintain comprehensive documentation of source data lineage, mapping logic, and cleaning procedures. This metadata is essential for ensuring transparency, reproducibility, and trust in the data.

- Establish a Durable Governance Framework: Formal governance is critical for long-term success. This involves defining data ownership, access policies, and update procedures. Key roles include Data Stewards (clinical or business experts responsible for a data domain) and Data Custodians (IT teams managing the infrastructure). The framework must also ensure compliance with regulations like GDPR and HIPAA. The CODE-EHR best practice framework offers excellent guidance, and our Federated Governance Complete Guide explains how to manage this in distributed environments.

From Harmonized Data to Actionable Insights

A harmonized dataset is not the end goal; it is the catalyst that transforms fragmented information into actionable insights for patient care, population health, and precision medicine. This unified view allows us to generate high-quality real-world evidence (RWE), improve population health management by identifying trends and risk factors, and advance precision medicine with richer, more complete patient data.

How to Improve Patient Outcome Research by harmonizing disparate electronic health records

Harmonizing disparate electronic health records has a profound and direct impact on the quality and scope of patient outcome research.

- Improve Generalizability and Statistical Power: By integrating data from multiple institutions, researchers can create larger, more diverse patient cohorts. Analyzing data from 240,214 patients across three EHRs, for example, yields far more statistically powerful and generalizable findings than a single-institution study, which may be biased by local population demographics and practice patterns.

- Enable Longitudinal Analysis of Disease Progression: A harmonized dataset that spans years or even decades allows researchers to track chronic conditions over time. This makes it possible to identify factors influencing patient trajectories, model disease progression, and reveal insights into long-term health outcomes that are invisible in cross-sectional data.

- Inform Evidence-Based Clinical Practice: Research from harmonized EHRs provides real-world insights into how treatments perform in diverse, complex patient populations, as opposed to the highly controlled environment of a clinical trial. This evidence can directly inform and refine clinical guidelines, helping clinicians make more personalized, evidence-based decisions for different patient subgroups.

- Create and Apply Harmonized Outcome Measures: To overcome variability in clinical definitions, initiatives by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) have developed standardized, computable outcome measures for conditions like Depression, Atrial Fibrillation, and Asthma. Implementing these standards within a harmonized dataset allows for true, apples-to-apples comparison of patient outcomes across different health systems. Learn more about Clinical Data Interpretation.

Case Study in Action: Uncovering Cardiovascular Risk with Harmonized Data

A multi-site research network harmonized EHR data from five hospital systems, creating a cohort of 500,000 patients. By mapping diagnoses to SNOMED CT and lab results to LOINC, they were able to build a computable phenotype for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). By analyzing this longitudinal dataset, they discovered that patients with NAFLD had a 40% higher risk of developing atrial fibrillation over a 5-year period, even after controlling for traditional risk factors like obesity and hypertension. This novel real-world evidence, generated from previously siloed data, led to new screening recommendations for cardiologists treating patients with liver disease.

How to Address Health Disparities by harmonizing disparate electronic health records

Harmonization is a powerful tool for advancing health equity. Inconsistent or missing data on race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status in siloed EHRs makes it nearly impossible to systematically identify and address inequities in care.

- Identify and Quantify Care Gaps: Harmonized data allows for the robust analysis of health outcomes across diverse demographic groups. By combining data on large cohorts of White, African-American, and Hispanic/Latino patients, researchers can reliably pinpoint disparities in diagnosis rates, treatment patterns, and access to care.

- Promote Health Equity with Targeted Interventions: Accurately identifying which groups experience poorer outcomes is the first step toward fixing the problem. This evidence enables healthcare systems and policymakers to develop targeted interventions—such as culturally competent patient education programs or mobile screening clinics in underserved neighborhoods—as outlined in plans for health equity indicators.

- Analyze Social Determinants of Health (SDOH): Harmonization allows for the integration of clinical data with SDOH data. Incorporating geographic information like ZIP codes or census-tract data on income and education helps reveal how social and environmental factors influence health, providing a more holistic view of health disparities. Our blog on Data Linking explores this further.

The Power of Harmonized Data for Public Reporting

A repository built on harmonized data is a powerful tool for public accountability and quality improvement. The Wisconsin Collaborative for Healthcare Quality (WCHQ) provides a compelling example. Their repository includes data from 25 health systems, covering over 4 million patients.

This allows WCHQ to:

- Enable Statewide Quality Reporting: WCHQ calculates and publicly reports on over 25 quality metrics on their public-facing website. This transparency empowers patients to make informed choices and allows providers to benchmark their performance.

- Drive Quality Improvement: Public reporting creates a powerful incentive for healthcare organizations to improve performance. No organization wants to be at the bottom of the list, which spurs investment in quality improvement initiatives.

- Monitor and Address Disparities: The harmonized data allows WCHQ to stratify quality measures by race, insurance status, and location, revealing significant disparities and guiding targeted interventions to close these gaps.

Centralized vs. Federated Models: Choosing the Right Architecture

The WCHQ example uses a centralized model, where data is physically moved to a central repository. An alternative is the federated model.

- Centralized Model: Data is copied, transformed, and stored in a single location. Pros: Analytically powerful and easier to query once built. Cons: Poses significant data security risks, requires complex data sharing agreements, and many institutions are unable or unwilling to move patient data off-premises.

- Federated Model: Data remains securely at its source institution. A query is sent to each site, analysis is performed locally on the harmonized data, and only aggregated, non-identifiable results are returned. Pros: Maximizes data security and privacy, simplifying governance and accelerating collaboration. Cons: Can be more complex to set up and may limit certain types of analysis.

Such repositories and networks, securely managed in a Trusted Research Environment, transform raw data into a public good that fosters accountability and a more equitable society.

Conclusion

The journey to harmonizing disparate electronic health records is complex, but not impossible. By following a systematic blueprint—from defining goals and assessing data to adopting common models and implementing governance—organizations can transform fragmented data silos into a unified, powerful resource. This opens up immense potential, enabling more generalizable research, deeper insights into disease progression, and evidence-based clinical practices. Crucially, it empowers us to identify and address health disparities, while centralized repositories can drive system-wide quality improvement through public reporting.

At Lifebit, we believe that harmonizing disparate electronic health records is not just a technical necessity but a cornerstone of modern research and health equity. Our next-generation federated AI platform is specifically designed to enable secure, compliant, and efficient harmonization and analysis across disparate data sources, without the need to move sensitive data. This approach leverages technologies like Trusted Research Environments, the Trusted Data Lakehouse, and our Real-time Evidence & Analytics Layer to ensure data privacy while opening up its full potential for real-world evidence generation and AI-driven pharmacovigilance.

The future of healthcare research and delivery hinges on our ability to integrate and understand the vast ocean of patient data. By embracing robust strategies for harmonization, we can bridge the gaps in our electronic health records, accelerating findy and ultimately improving health outcomes for all.

Find how to securely harmonize your data with a federated platform: https://lifebit.ai/trusted-research-environments/