Preclinical vs. Clinical Biomarkers: Understanding Their Impact on Drug Efficacy

Stop R&D Waste: How Drug Efficacy Biomarkers Prevent $1B Failures

Drug efficacy biomarkers are measurable indicators that tell us whether a treatment is actually working in the body. They range from specific molecules like proteins or gene sequences to physiological parameters like blood pressure or viral load—and they’re changing how we develop, test, and approve new medicines.

Key Types of Drug Efficacy Biomarkers:

- Pharmacodynamic (PD) biomarkers – Measure the biological response to a drug (e.g., receptor occupancy, enzyme activity)

- Predictive biomarkers – Identify which patients are most likely to respond to a specific therapy (e.g., HER2 status for breast cancer)

- Monitoring biomarkers – Track treatment response over time (e.g., HIV viral load, HbA1c for diabetes)

- Prognostic biomarkers – Predict disease progression independent of treatment (e.g., tumor stage markers)

- Safety biomarkers – Detect early signs of drug toxicity (e.g., liver enzymes, kidney function tests)

These biomarkers matter because they can predict drug efficacy more quickly than conventional clinical endpoints like survival or disease progression—which can take years to measure. In fact, biomarker selection is the second-highest challenge for phase I trials, cited by 35% of drug developers in recent surveys.

The stakes are high. Qualifying a single biomarker like plasma fibrinogen took nearly 4.5 years and cost approximately $1.4 million in investment. But when done right, biomarkers can dramatically reduce late-stage failures, accelerate regulatory approval, and ensure the right patients get the right treatments.

I’m Maria Chatzou Dunford, CEO and Co-founder of Lifebit, where we’ve spent over 15 years building federated AI platforms that integrate multi-omic and biomedical data to accelerate drug efficacy biomarkers findy across secure, compliant environments. Our work empowers pharmaceutical and public health organizations to turn complex datasets into actionable insights—faster and more safely than ever before.

Drug efficacy biomarkers terms you need:

- Precision health data

- Which companies offer services for building a biomedical knowledge graph?

- Who are the leading providers of AI-powered biomarker discovery services?

7 Drug Efficacy Biomarkers to Hit Clinical Endpoints Faster

To steer the complex world of drug development, we rely on the FDA-NIH BEST Resource, which provides a standardized glossary for biomarker categories. Understanding these types is the first step in establishing a “Context of Use” (COU)—the specific clinical scenario where a biomarker will be applied. A COU defines the precise role of the biomarker, the population in which it will be used, and the clinical trial setting it supports.

| Biomarker Type | Definition | Example in Efficacy |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic | Identifies the presence of a disease or subtype. | PCR-based viral nucleic acid tests for COVID-19. |

| Monitoring | Assessed serially to track disease status or medical response. | HIV RNA viral load to monitor antiviral therapy. |

| Pharmacodynamic | Shows that a biological response has occurred in a person exposed to a drug. | Increased INR for patients on warfarin. |

| Predictive | Identifies individuals more likely to experience a favorable or unfavorable effect from a drug. | HER2 expression for trastuzumab efficacy in breast cancer. |

| Prognostic | Identifies the likelihood of a clinical event or disease progression. | Total Kidney Volume (TKV) in polycystic kidney disease. |

| Safety | Detects or predicts the likelihood of an adverse event. | Hepatic aminotransferases for drug-induced liver injury. |

| Susceptibility/Risk | Indicates the potential for developing a disease or condition. | BRCA1/2 mutations for breast cancer risk. |

Deep Dive into the BEST Categories

1. Diagnostic Biomarkers: These are essential for patient selection. For instance, in Alzheimer’s research, amyloid-beta PET imaging or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) levels of tau proteins are used to ensure that patients enrolled in a trial actually have the pathology the drug is designed to target. Without these, efficacy signals would be diluted by patients who have similar symptoms but different underlying causes.

2. Monitoring Biomarkers: These provide a continuous readout of a patient’s status. In chronic conditions like diabetes, HbA1c serves as a monitoring biomarker to assess the long-term efficacy of glucose-lowering agents. In oncology, the emergence of new mutations in circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) can monitor for the development of drug resistance, signaling the need for a change in therapy.

3. Pharmacodynamic (PD) Biomarkers: These are often called “proof-of-mechanism” markers. They answer the question: “Is the drug doing what it was designed to do at the molecular level?” For a kinase inhibitor, a PD biomarker might be the phosphorylation state of a downstream protein. If the drug is working, that phosphorylation should decrease. This is critical for dose-finding studies to ensure the drug reaches the target at a concentration that elicits a biological effect.

4. Predictive Biomarkers: These are the linchpin of precision medicine. They identify the specific subset of patients who will benefit from a drug. A classic example is the KRAS mutation status in colorectal cancer; patients with certain KRAS mutations do not respond to EGFR inhibitors, so the biomarker prevents them from receiving an ineffective and potentially toxic treatment.

5. Prognostic Biomarkers: These provide a baseline of the disease’s natural history. They help researchers understand the likely outcome for a patient regardless of the treatment. For example, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) levels can predict the risk of heart failure progression, allowing researchers to stratify patients by risk level to ensure balanced trial arms.

6. Safety Biomarkers: While the focus is often on efficacy, safety biomarkers like serum creatinine (for kidney function) or troponins (for cardiac injury) are vital for determining the therapeutic index. They allow for early detection of toxicity, often before clinical symptoms appear, protecting patient safety and preventing late-stage trial terminations.

7. Susceptibility/Risk Biomarkers: These are used primarily in prevention trials. By identifying individuals with a high genetic risk for a disease (like those with Lynch syndrome for colorectal cancer), researchers can test preventative therapies in the populations most likely to show a benefit.

At Lifebit, we help researchers harmonize these diverse data types—from physiological parameters like blood pressure to complex multi-omic profiles—to build a comprehensive picture of drug performance. By integrating these markers into a unified analytical framework, we enable a more holistic understanding of how a drug interacts with the human body.

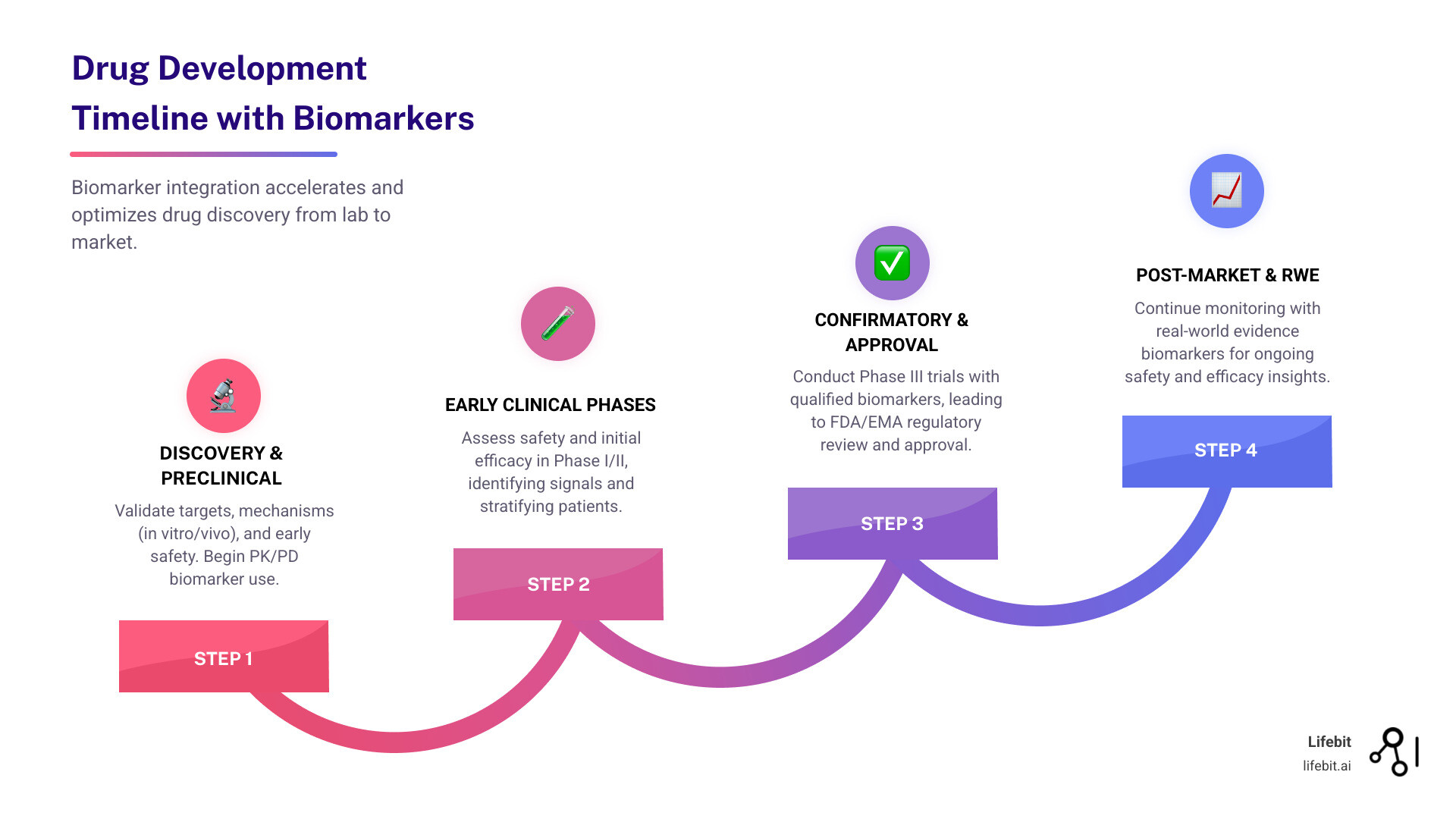

Fix the ‘Valley of Death’: Predict Human Efficacy Before Phase I

One of the most dangerous phases in drug development is the “valley of death” between laboratory models and human trials. Preclinical biomarkers are identified in in vitro (cell lines, organoids) and in vivo (animal models like mice or zebrafish) settings. While these models are essential for early safety and mechanism of action studies, they don’t always translate perfectly to human biology. This lack of translation is a primary driver of the high failure rate in Phase II trials, where drugs first face the test of efficacy in humans.

The Three Pillars of Survival in Phase I

To bridge this gap, researchers often utilize the “Three Pillars” framework for drug development. This approach uses drug efficacy biomarkers to confirm three critical requirements in early human trials:

- Pillar 1: Exposure at the Target. Does the drug reach the intended site of action (e.g., crossing the blood-brain barrier) at a concentration sufficient to interact with the target?

- Pillar 2: Binding to the Target. Does the drug actually bind to the intended molecular target (e.g., a receptor or enzyme) in humans as it did in animal models?

- Pillar 3: Functional Pharmacological Activity. Does the binding lead to the intended biological response (e.g., inhibition of a signaling pathway)?

By using biomarkers to answer these three questions in Phase I, developers can gain “Proof of Mechanism” (PoM) long before they reach “Proof of Concept” (PoC) in Phase II. This early validation is the best defense against the “valley of death.”

Utilizing Early-Stage Drug Efficacy Biomarkers to Prevent Late-Stage Failure

Why do so many drugs fail in Phase III? Often, it’s because the wrong dose was selected or the drug didn’t actually engage the target in humans. Early-stage drug efficacy biomarkers provide an insurance policy against these billion-dollar mistakes.

In neuroscience, for example, transcriptomic processes are used to track failures in gene expression related to amyloid and tau biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease. According to Scientific research on Alzheimer’s transcriptomics, these early signals can provide a “proof of concept” long before cognitive decline can be measured. By using biomarkers as alternatives to the traditional Maximum Tolerable Dose (MTD) approach—especially in cell and gene therapies—we can de-risk R&D investments and focus on the most promising candidates.

Furthermore, the use of Pharmacokinetics (PK) parameters like AUC (Area Under the Curve) and Cmax (Maximum Concentration) as surrogate endpoints allows for the comparison of efficacy between different formulations or generic agents. By utilizing Research on the impact of biomarkers in early clinical development, we can see how mechanism-driven endpoints in early studies help bridge this gap, ensuring that the “proof of concept” seen in a mouse translates into a real-world cure.

Stop One-Size-Fits-All: Use Patient Stratification to Prove Efficacy Faster

The era of the “simple” clinical trial is over. Today, we use “Master Protocols” to run umbrella trials and basket trials that test multiple drugs or multiple disease subtypes simultaneously. This requires advanced patient stratification, moving away from broad disease definitions toward molecularly defined patient populations.

The Power of Master Protocols

- Basket Trials: These trials test a single investigational drug across multiple different diseases that share a common biomarker. For example, a drug targeting a specific BRAF mutation might be tested in patients with melanoma, lung cancer, and colorectal cancer simultaneously. This allows for the discovery of efficacy signals in rare indications that might never have been studied in a standalone trial.

- Umbrella Trials: These focus on a single disease but test multiple different drugs based on the specific molecular profile of the patient’s tumor. In Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC), an umbrella trial might assign one patient to an EGFR inhibitor, another to an ALK inhibitor, and a third to immunotherapy, all within the same study framework.

Enrichment Strategies for Success

Patient stratification is often achieved through “enrichment” strategies. Prognostic enrichment involves selecting patients who are more likely to experience a disease-related event (e.g., choosing high-risk cardiovascular patients), which increases the statistical power of the trial. Predictive enrichment involves selecting patients who are more likely to respond to the drug based on a specific biomarker (e.g., HER2+ status).

Take NSCLC as an example. By using clinicogenomic databases, researchers can match patients to therapies based on actionable genomic alterations that might be missed by standard testing. Research on NSCLC clinicogenomics shows that this targeted approach leads to significantly better clinical outcomes. To manage this complexity, we use:

- Adaptive Trial Designs: Allowing for modifications to the trial (such as dropping an ineffective arm or adjusting the sample size) based on interim biomarker data.

- Bayesian Methods: Using probability to optimize study outcomes even with smaller patient populations, which is particularly useful in rare disease research.

- Companion Diagnostics (CDx): These are FDA-cleared or approved medical devices that provide information essential for the safe and effective use of a corresponding drug. Developing a CDx alongside the drug ensures that every patient enrolled has the specific molecular profile the drug targets, maximizing the chance of proving efficacy.

Cut the $1.4M Validation Cost: Navigate FDA Biomarker Qualification Faster

Validation isn’t just a scientific hurdle; it’s a massive financial and regulatory one. Qualifying a biomarker through the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) Biomarker Qualification Program (BQP) or the EMA’s qualification process is a marathon, not a sprint. However, the long-term benefits of qualification far outweigh the initial costs.

The Three Stages of FDA Qualification

- Letter of Intent (LOI): This is the first formal step where the requester describes the biomarker, the proposed Context of Use (COU), and the drug development need. The FDA reviews this to determine if the biomarker has the potential to provide significant value to drug development.

- Qualification Plan (QP): If the LOI is accepted, the requester submits a QP. This document outlines the data collection and analysis plan intended to support the qualification. It includes the clinical trial designs, the analytical validation of the assay, and the statistical methods to be used.

- Full Qualification Package (FQP): This is the final submission containing all the data and analysis. If the FDA agrees that the evidence supports the COU, the biomarker is “qualified.”

The Impact of the 21st Century Cures Act

The 21st Century Cures Act has helped by mandating transparency and providing structured pathways for Drug Development Tools (DDTs). It requires the FDA to publish the status of biomarkers in the qualification process, which encourages collaboration and prevents redundant efforts. Once a biomarker is qualified, it can be used across multiple drug programs without needing to resubmit the same foundational data. This “use once, apply many” model is the key to reducing the overall cost of drug development.

Consider the case of plasma fibrinogen. It took nearly 4.5 years from the initial Letter of Intent (LOI) in 2011 to the issuance of draft guidance in 2015. The investment? Approximately $1.4 million. This process requires a defined Context of Use (COU) and an evidentiary framework that proves the biomarker is “reasonably likely” to predict a clinical outcome. While the cost is high, the ability to use fibrinogen as a qualified endpoint in COPD trials has since saved the industry tens of millions in trial costs. You can learn more about these requirements at the FDA Biomarker Qualification Program.

Find Efficacy Signals in Hours with Federated AI and Multi-Omics

The future of drug efficacy biomarkers lies in our ability to process vast amounts of data in real-time. Advanced technologies like AI, multi-omics, and liquid biopsies are revolutionizing the field, moving us from single-marker analysis to complex biological signatures.

The Multi-Omic Revolution

Integrating genomics, proteomics, and transcriptomics provides a “holistic” view of disease. While a single genetic mutation might suggest a risk, the proteome (the entire set of proteins expressed) tells us what is actually happening in the body right now. Research on molecular profiling for precision cancer therapies highlights how this deep profiling identifies actionable targets that single-gene tests miss. For example, transcriptomics can reveal how a drug changes gene expression patterns across entire metabolic pathways, providing a much more sensitive measure of efficacy than a simple blood test.

Liquid Biopsies: Real-Time Monitoring

Liquid biopsies detect circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), RNA, or extracellular vesicles in blood. These non-invasive tests allow for real-time monitoring of treatment response without the need for painful and risky tissue biopsies. In oncology, a drop in ctDNA levels can indicate that a treatment is working weeks or even months before a tumor shrinkage is visible on a CT scan. This allows for rapid “go/no-go” decisions in early-phase trials.

Federated AI: Solving the Data Silo Problem

This is where Lifebit excels. One of the biggest hurdles in biomarker discovery is that the most valuable data is often locked in secure silos across different hospitals, countries, and research institutions. Moving this data is often impossible due to privacy regulations like GDPR or HIPAA.

Our platform utilizes Federated AI, which enables secure, real-time access to global biomedical data without moving the data itself. Instead of bringing the data to the model, we bring the model to the data.

- Local Training: The AI model is trained locally on the secure server where the data resides.

- Parameter Aggregation: Only the “insights” (mathematical weights) are sent back to a central server.

- Global Model Update: These insights are combined to create a more powerful, global model that has “seen” data from five continents without ever compromising patient privacy.

By using Trusted Research Environments (TREs) and AI-driven analytics, we can identify novel biomarker signatures from high-throughput screening data in hours rather than months. This allows for large-scale, compliant research that ensures biomarker signatures are validated across diverse, real-world populations, making them more robust and reliable for clinical use.

Drug Efficacy Biomarkers: Your Top Regulatory and Technical Questions Answered

What is the difference between preclinical and clinical biomarkers?

Preclinical biomarkers are used during the discovery and early development phases in laboratory settings (cell lines, organoids) and animal models. Their primary role is to evaluate drug safety, mechanism of action, and initial efficacy signals to justify moving into human trials. Clinical biomarkers are used in human trials to monitor patient response, assess safety in humans, and stratify patients into groups most likely to benefit from the therapy. The transition from preclinical to clinical is the most critical step in the R&D pipeline.

How do regulatory bodies like the FDA qualify biomarkers for efficacy?

The FDA uses the Biomarker Qualification Program (BQP), a three-stage process involving a Letter of Intent (LOI), a Qualification Plan (QP), and a Full Qualification Package (FQP). Qualification means the FDA agrees that the biomarker and its specific Context of Use (COU) are reliable for use in drug development and regulatory review. Once qualified, the biomarker can be used in any drug development program for that specific COU without the need for additional validation data.

Can AI and multi-omics improve the identification of efficacy biomarkers?

Absolutely. AI and machine learning can analyze massive, complex multi-omic datasets (genomics, proteomics, metabolomics, etc.) to identify subtle patterns and correlations that human researchers might miss. This leads to more precise patient stratification, more accurate prediction of drug response, and a significantly higher success rate for clinical trials. AI is particularly adept at identifying “composite biomarkers”—signatures made up of multiple different markers that together provide a much stronger signal than any single marker alone.

What is a surrogate endpoint, and how does it relate to biomarkers?

A surrogate endpoint is a biomarker that is intended to substitute for a clinical endpoint. It is expected to predict clinical benefit based on epidemiologic, therapeutic, or other scientific evidence. For example, blood pressure is a surrogate endpoint for the clinical endpoint of stroke or heart attack. The FDA allows for accelerated approval of drugs based on surrogate endpoints that are “reasonably likely” to predict clinical benefit, provided the manufacturer conducts post-marketing trials to confirm the actual clinical benefit.

How does Federated Learning protect patient privacy in biomarker research?

Federated Learning ensures that sensitive patient data never leaves its original, secure environment. Instead of centralizing data, the analysis is performed locally at each site (e.g., a hospital or biobank). Only the non-identifiable model updates are shared and aggregated. This allows researchers to achieve the statistical power of a massive, global dataset while remaining fully compliant with strict data privacy laws like GDPR.

Start Finding Better Drug Efficacy Biomarkers with Lifebit Today

The journey from a biological “hunch” to a qualified drug efficacy biomarker is long and expensive, but it is the only way to build the next generation of precision therapies. At Lifebit, we believe that the key to open uping this potential lies in secure, global collaboration.

Our federated AI platform allows biopharma companies and governments to analyze multi-omic data where it lives, ensuring compliance while delivering real-time insights. By bridging the gap between preclinical findy and clinical success, we are helping to turn the promise of personalized medicine into a reality for patients everywhere.