Don’t Be a Guinea Pig for Federated Cohort Browsers

What is a Federated Cohort Browser and Why Did Google Build It?

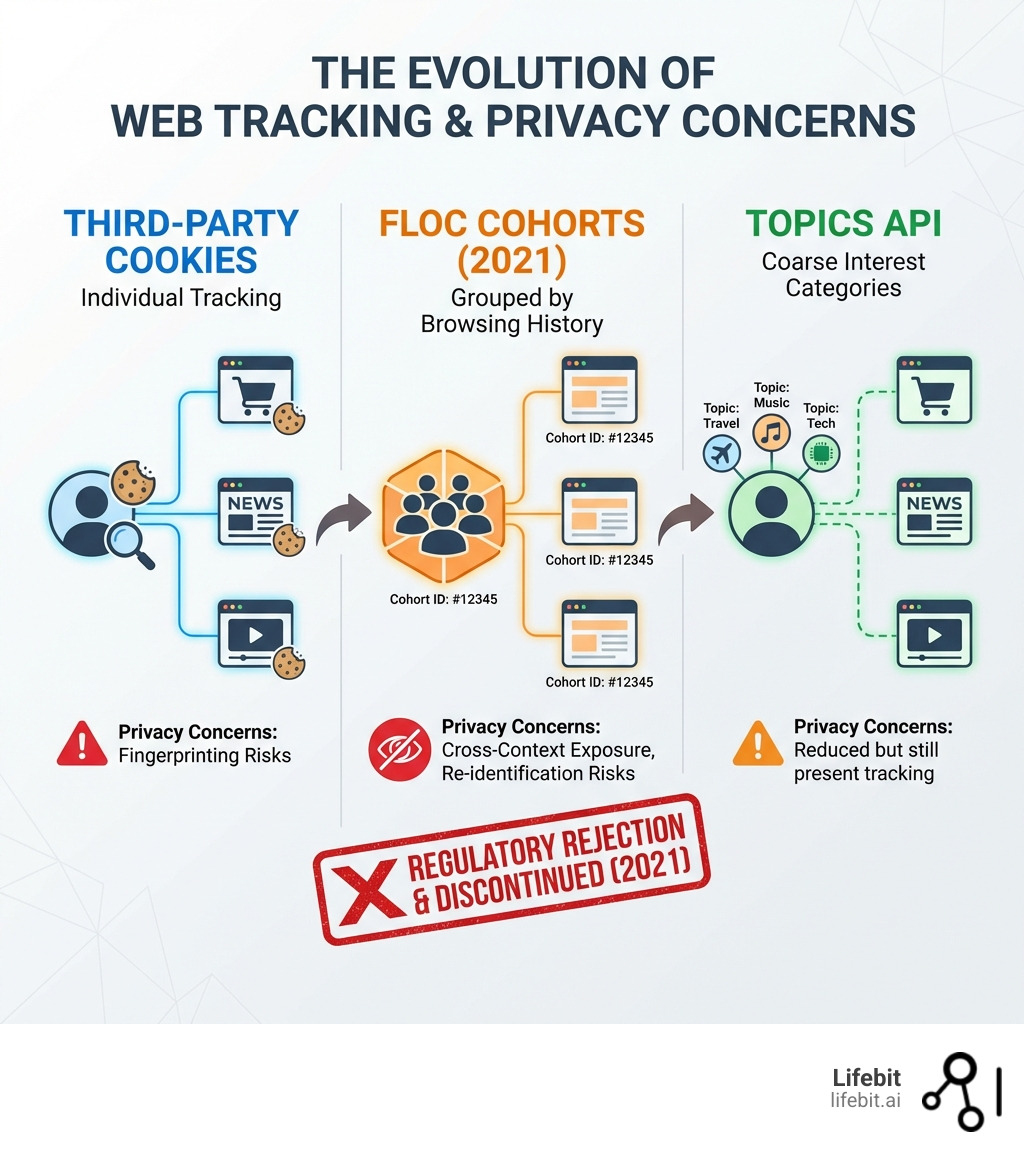

A federated cohort browser was Google’s controversial attempt to replace third-party cookies with a new tracking system called FLoC (Federated Learning of Cohorts). Instead of tracking you individually, it grouped users into “cohorts” of thousands based on browsing history—then shared that cohort ID with every website you visited. This initiative was part of a broader strategy known as the Privacy Sandbox, which aimed to reconcile the needs of the multi-billion dollar digital advertising industry with the increasing demand for user privacy and data protection.

Quick Facts:

- What it was: A browser feature that assigned you to an interest group based on your web activity

- Who built it: Google, as part of the Privacy Sandbox initiative

- Why it failed: Privacy advocates, competitors, and regulators rejected it for creating new tracking risks

- What replaced it: The Topics API, launched in January 2022

- Current status: Discontinued after testing from March to August 2021

The technology promised “privacy-preserving” ad targeting. But critics called it a “concrete breach of user trust” and a system that “should not exist,” according to the Electronic Frontier Foundation. Major browsers like Brave, Vivaldi, and Edge refused to implement it. By April 2021, Google stood nearly alone. The fundamental tension lay in the fact that while FLoC removed the individual identifier (the cookie), it replaced it with a group identifier that could still be used to profile users with startling accuracy.

Why did this matter? Because one wrong turn in browser technology affects billions of users—often without their knowledge or consent. Google tested FLoC on 0.5% of Chrome users across 10 countries without notification. Those users became guinea pigs in an experiment that privacy experts and antitrust regulators quickly condemned. The experiment highlighted the immense power that browser developers hold over the digital ecosystem and the ethical responsibilities that come with that power.

I’m Maria Chatzou Dunford, CEO of Lifebit, where we’ve spent years building federated cohort browser tools for biomedical research that actually protect privacy—enabling secure analysis across siloed datasets without moving sensitive data. That experience taught us what truly privacy-preserving federated systems look like, and FLoC wasn’t it. In the world of genomics, “federated” means the data stays behind a firewall and only the insights move. In Google’s FLoC, the “federated” label was used more as a marketing term for local computation, which didn’t necessarily prevent the leakage of sensitive behavioral patterns.

Federated cohort browser vocab explained:

When we talk about a federated cohort browser, we are looking at a specific chapter in the “Cookiepocalypse.” For decades, the web relied on third-party cookies to track users across different sites. These cookies allowed advertisers to build detailed profiles of individuals, tracking their movements from a news site to a shoe store to a medical blog. As privacy regulations like GDPR and CCPA tightened and users grew weary of being followed by that one pair of shoes they looked at once, Google needed a replacement that would satisfy regulators while keeping their ad revenue intact.

Enter the Federated Learning of Cohorts (FLoC). The idea was to move the “tracking” from the advertiser’s server directly into your browser. Instead of a website knowing exactly who you are, it would only see your “Cohort ID.” This was intended to provide “k-anonymity,” a property where an individual cannot be distinguished from a group of at least ‘k’ individuals. Google set the target for ‘k’ at several thousand users per cohort.

To do this, Google utilized the SimHash algorithm. This algorithm is a type of locality-sensitive hashing. It looked at the domains you visited and compressed that data into a short, four-character label (like 52P9). Unlike traditional hashes where a small change in input results in a completely different output, SimHash ensures that similar inputs (similar browsing histories) result in similar or identical hashes. The “federated” part of the name implied that the learning happened locally on your device, though critics noted that it didn’t actually use traditional federated learning techniques, which usually involve training a global model across many decentralized devices. At Lifebit, we use federated data analysis to keep sensitive genomic data in place while allowing researchers to run queries, which is a much more robust application of the “federated” philosophy, ensuring that raw data is never exposed to the central server or other participants.

How FLoC grouped users into cohorts based on history

The mechanics of the federated cohort browser were surprisingly simple but deeply invasive. Your Chrome browser would look at your last week of web activity—the blogs you read, the stores you visited, the news sites you frequented—and run that list through the SimHash algorithm. This process was entirely automated and happened in the background without user intervention.

- Local Computation: All the “thinking” happened on your laptop or phone. Your raw history was never supposed to leave the device. Google argued this was a massive privacy win because the “master list” of your browsing history stayed with you.

- Cohort ID: Based on your history, you were assigned a number. If you and 5,000 other people all visited “Classic Rock” and “Hiking” sites, you’d all get the same ID. This ID was then made available to any website you visited via a simple Javascript API call.

- Weekly Updates: Your interests change, so your ID changed every week. This was meant to reflect your current interests, but it also meant that over time, a tracker could observe how your cohort ID changed, potentially revealing even more about your life transitions (e.g., moving from a “wedding planning” cohort to a “baby supplies” cohort).

While this sounds like a win for privacy, it created a “behavioral credit score” that you carried from site to site. It essentially broadcasted a summary of your personality and habits to every server you connected to. For a deeper look at how aggregate data can be handled safely without these risks, check out our Federated Analytics Ultimate Guide.

The intended purpose of the federated cohort browser

Google’s goal was to prove that you could have effective advertising without individual tracking. In January 2021, Google claimed that FLoC was at least 95% as effective as third-party cookies in terms of conversions per dollar spent. They wanted to maintain the massive revenue of the ad industry while appearing to respect user anonymity. This was a high-stakes gamble; if Google could convince the industry that FLoC worked, they could deprecate cookies and solidify their position as the primary architect of web privacy.

By grouping you with thousands of others, Google argued you were “hidden in a crowd.” This was their pitch for the future of federated data sharing: you get the benefits of personalized content and ads without the “creepy” feeling of being watched as an individual. However, the “crowd” was not as anonymous as Google suggested, as the specific combination of a cohort ID and other browser metadata often left users uniquely identifiable.

The Privacy Scandal: Why the Industry Said “No FLoCing Way”

The backlash was immediate and fierce. While Google touted anonymity, the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) launched a campaign titled “Google’s FLoC is a Terrible Idea.” The core of the EFF’s critique of FLoC was that it didn’t actually stop tracking—it just changed the method and centralized the power within the browser itself. The EFF even created a tool called “Am I FLoCed?” to help users check if they were part of Google’s secret trials.

Privacy experts pointed to two massive flaws that undermined the entire project:

- Fingerprinting: This is the practice of combining many small pieces of information to create a unique identifier for a user. By giving every user a Cohort ID, Google actually made it easier to identify individuals. If a tracker already knows a few things about your device (like your screen resolution, installed fonts, or battery level), adding a Cohort ID provides the “missing link” to uniquely identify you. A cohort ID contains several bits of entropy; when added to existing fingerprinting techniques, the probability of uniquely identifying a user approaches 100%.

- Cross-Context Exposure: This occurs when information from one part of your life is leaked to another. If you visit a site about a sensitive medical condition, that site could now see your Cohort ID and realize you also frequent high-end luxury car sites. It links your private health interests with your financial status in a way that was previously difficult without cross-site cookies. Furthermore, if you log into a site with your real name (like a social network), that site can now associate your real identity with your Cohort ID, and by extension, your entire week’s browsing history summary.

At Lifebit, we solve these types of exposure risks through a Trusted Research Environment, where data never leaves its secure “home,” and only the results of an analysis are shared—not the raw identifiers or behavioral summaries. This “data-to-code” model is the polar opposite of FLoC’s “broadcast-the-summary” model.

Anti-competitive practices and the federated cohort browser controversy

Beyond privacy, the federated cohort browser sparked an antitrust firestorm. The UK’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) and several US states raised concerns that FLoC would turn Google into the ultimate “gatekeeper” of the web. The concern was that Google, by controlling the browser and the cohort assignment algorithm, would have an unfair advantage over other advertising networks that no longer had access to the same level of granular data.

If Google controlled the cohorts, they controlled the audience. Smaller ad-tech firms argued that by removing cookies and replacing them with a system only Google fully understood and controlled, Google was effectively killing its competition. This raised serious questions about federated governance and who should have the right to define “interest groups” for the entire internet. Regulators were worried that FLoC would reinforce Google’s dominant position in the ad market by making the browser the central point of control for all advertising data.

Organizations and browser vendors that opposed FLoC

It wasn’t just activists who were upset; it was almost the entire tech industry. The rejection was so widespread that it became a rare moment of industry-wide consensus against a Google-led initiative. By April 2021, the list of those who refused to implement FLoC included:

- Browser Vendors: Brave, Vivaldi, Microsoft Edge, and Mozilla Firefox all declined to use the technology. Brave went as far as to call FLoC “a step in the wrong direction” for privacy. Apple’s Safari team also signaled they would not support any technology that enabled cross-site tracking, even in aggregate form.

- Search Engines: DuckDuckGo updated its Chrome extension to specifically block FLoC, arguing that it was a “surveillance-by-default” mechanism.

- Platforms: GitHub and WordPress (which powers 40% of the web) moved to disable FLoC by default on their sites. WordPress proposed treating FLoC as a security concern, effectively opting out millions of websites automatically.

- E-commerce: Major retailers expressed concern that FLoC would allow competitors to “poach” their customers by targeting users in the same interest cohorts.

Even the W3C (the World Wide Web Consortium) saw significant pushback in its business groups. The Technical Architecture Group (TAG) of the W3C issued a finding that the proposal did not sufficiently protect user privacy. For those interested in how a truly collaborative and open system should work, our Federated Research Environment Complete Guide outlines a better path for data cooperation that respects individual sovereignty and institutional security.

The Timeline of a Failed Experiment: From Testing to Discontinuation

The life of the FLoC federated cohort browser was short but chaotic. It moved from a theoretical whitepaper to a global trial and then to the “tech graveyard” in less than two years. This rapid rise and fall serves as a case study in how not to launch a new web standard.

| Feature | Third-Party Cookies | FLoC (Federated Learning of Cohorts) |

|---|---|---|

| Identification | Individual (Unique ID) | Group (Cohort ID) |

| Data Storage | External Servers | Local Browser |

| Cohort Size | N/A | Several thousand users |

| Update Frequency | Real-time | Weekly |

| Effectiveness | 100% (Baseline) | 95% (Google Claim) |

| User Consent | Opt-in/Opt-out (GDPR) | Automatic in Trial |

The trial began in March 2021 with Chrome 89, affecting 0.5% of users in 10 countries (including the USA, Canada, Brazil, and Australia). However, Google notably excluded the European Union from the initial trial, likely due to fears of violating the GDPR’s strict requirements for processing personal data and the ePrivacy Directive’s rules on accessing information on a user’s device. This exclusion was a tacit admission that FLoC might not meet the high bar of European privacy law. For a full understanding of how modern platforms handle such complexities, see our Federated Data Platform Ultimate Guide.

Why Google ultimately abandoned FLoC development

By July 2021, the writing was on the wall. The combination of regulatory pressure from the CMA, which had opened a formal investigation into the Privacy Sandbox, and the total lack of adoption from other Chromium-based browsers made FLoC a “dead tech walking.” Google realized that a tracking standard only supported by one browser—even the most popular one—would not be enough to sustain the global advertising ecosystem.

Google officially announced it was abandoning FLoC in January 2022. The experiment failed because it tried to serve two masters: the privacy of the user and the profit of the advertiser. In the end, it satisfied neither. Advertisers were worried about the loss of precision, and users were worried about the new, more subtle forms of tracking. The failure of FLoC forced Google to rethink its entire approach to the Privacy Sandbox, leading to the development of the Topics API, which attempted to address the most glaring flaws of its predecessor.

How users and website administrators opted out of FLoC

During the height of the FLoC trial, a “digital resistance” formed. Website admins didn’t want their sites used to calculate user cohorts, as they felt it was a violation of their visitors’ trust. To opt out, they had to send a specific HTTP header in their server responses:

Permissions-Policy: interest-cohort=()

This simple line of code told Google’s crawler and the Chrome browser, “Don’t use my site’s data to profile my visitors or include them in any cohort calculations.” Within weeks of FLoC’s launch, thousands of major sites, including Amazon and The New York Times, implemented this header. This level of control is vital in sensitive fields like genomics, where federated technology in population genomics must allow for strict opt-out and permission controls to maintain the integrity of the research and the privacy of the participants. The FLoC opt-out mechanism was a precursor to the more sophisticated permission systems we see in modern federated architectures today.

Life After FLoC: The Rise of the Topics API

Google didn’t give up on the Privacy Sandbox; they just went back to the drawing board. They needed a system that was less “tracky” than FLoC but more useful than nothing. The result was the Topics API, which was designed to be a more transparent and less granular alternative to the federated cohort browser concept.

The Topics API is the successor to FLoC. It is designed to be much simpler and less prone to fingerprinting. Instead of a complex, weekly-calculated Cohort ID that could represent any combination of thousands of interests, your browser determines about five “topics” (like “Fitness,” “Travel,” or “Autos”) that represent your top interests for the week based on your browsing history. When you visit a site that supports the Topics API, the browser shares three of these topics—one from each of the past three weeks—with the site and its advertising partners.

This shift mirrors the move toward more specialized and controlled data handling we see in federated learning for precision medicine, where the focus is on specific, actionable insights rather than broad, “noisy” tracking. In medicine, we don’t need to know everything about a patient; we just need the specific data points relevant to their treatment. Similarly, the Topics API tries to provide just enough information for relevant advertising without revealing a user’s entire digital life.

How Topics API differs from its predecessor

The Topics API fixes several of FLoC’s “original sins” by introducing several layers of protection:

- No Sensitive Categories: Google curated a list of topics (initially around 350) that explicitly excludes sensitive subjects like race, religion, sexual orientation, or medical conditions. In FLoC, because the cohorts were generated by an unsupervised algorithm (SimHash), there was no way to prevent the creation of a “sensitive” cohort.

- Transparency and Control: Users can see exactly which topics Chrome has assigned to them by looking in the browser settings. They can delete specific topics they don’t like or turn the entire feature off. This is a massive improvement over FLoC, where the Cohort ID was an opaque string of characters that meant nothing to the average user.

- Reduced Entropy: Because there are only a few hundred possible topics (compared to over 30,000 potential cohorts in FLoC), it provides much less “entropy” for fingerprinters to use. It is much harder to uniquely identify someone based on the fact that they like “Cooking” and “Dogs” than it is with a specific, high-entropy Cohort ID.

- Epoch-Based Rotation: Topics are calculated in “epochs” (currently one week). The browser only shares a small subset of topics, and it adds a 5% chance of returning a completely random topic to further confuse potential trackers. This “differential privacy” approach is a hallmark of modern secure data systems.

These improvements are similar to the key features of a Federated Data Lakehouse, where transparency, granular control, and the principle of least privilege are built into the architecture from day one. While the Topics API is still controversial among some privacy purists, it represents a significant step toward a more balanced web ecosystem than the original federated cohort browser ever could.

Frequently Asked Questions about Federated Cohort Browsing

What was the primary criticism of FLoC?

The biggest issue was fingerprinting. Critics argued that adding a Cohort ID to a user’s browser made it significantly easier for trackers to uniquely identify individuals by combining that ID with other device data. Additionally, the lack of user consent during the initial trials and the potential for “cross-context exposure” of sensitive interests were major points of contention.

Is the Topics API safer than FLoC?

Yes, generally. It provides more user control, excludes sensitive categories by design, and offers much less specific data to advertisers. By using a human-curated taxonomy of topics rather than an automated hashing algorithm, it prevents the accidental creation of cohorts based on sensitive personal attributes. It also introduces “noise” into the data to make individual tracking more difficult.

Can I still be tracked without third-party cookies?

Absolutely. While cookies are going away, “fingerprinting” (using your IP address, font list, and browser version) and “first-party data” (information you give directly to a site when you log in) are still very much alive. Advertisers are also exploring “probabilistic modeling” and “clean rooms” to continue targeting users in a post-cookie world.

Why did Google exclude the EU from FLoC trials?

Google never officially stated the reason, but it is widely believed that FLoC did not comply with the GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation). Under GDPR, processing personal data requires a clear legal basis, and “legitimate interest” is often not enough for invasive tracking. Furthermore, the ePrivacy Directive requires explicit consent for storing or accessing information on a user’s device, which FLoC’s automatic assignment did not provide.

How does Lifebit’s federated approach differ from Google’s?

Google’s FLoC was designed to broadcast a summary of user behavior to the world for advertising purposes. Lifebit’s federated approach is designed to keep highly sensitive biomedical data secure within its original environment. We bring the analysis to the data, rather than moving the data (or even a summary of it) to the analyst. This ensures that privacy is maintained at the highest level required for clinical and genomic research.

Conclusion

The saga of the federated cohort browser serves as a cautionary tale for the tech industry. It reminds us that “federated” is not a magic word that automatically grants privacy—it requires careful implementation, industry-wide consensus, and a genuine commitment to user agency. The failure of FLoC was not a failure of the federated concept itself, but rather a failure of a specific implementation that prioritized the needs of the advertising market over the fundamental rights of the individual.

As we move into the post-cookie era, the lessons of FLoC are more relevant than ever. We are seeing a shift toward “Privacy-Enhancing Technologies” (PETs) that use encryption, differential privacy, and federated architectures to enable data utility without compromising security. This is the same philosophy that drives our work at Lifebit.

At Lifebit, we believe the future of data is federated, but it must be built on trust. Our federated AI platform allows organizations to collaborate on the world’s most sensitive biomedical and multi-omic data while ensuring that the data never moves and privacy is never compromised. Whether you are a government agency or a biopharma researcher, we provide the Federated Trusted Research Environment needed to turn data into cures without making anyone a “guinea pig.” The goal is to enable global collaboration that can solve the world’s most complex health challenges while respecting the sanctity of individual data.

Ready to see what real federated privacy looks like?

Learn how Lifebit powers secure global research